Music sometimes builds the most emotionally appropriate bridges, as we contemplate the fragile nature of our humanity. In the 1990s, Vedran Smailović, a cellist from Bosnia and Herzegovina who now lives in northern Ireland, played music among the ruins during the siege of Sarajevo in the Balkan War. His musical gesture inspired a solo work for cello as well as a children’s book by a Canadian author and a novel.

Twenty-two years ago on the day after a mortar attack during the Balkan War struck a bakery and killed 22 people in Sarajevo, Smailovic started a 22-day protest vigil, playing one of the most hauntingly elegiac pieces of the Baroque era at the hour (10 a.m.) when the attack occurred. Indeed, the Adagio in G minor by the 18th century Italian composer Tomaso Albinoni touched deep human root of music’s power.

In 2012, on the 20th anniversary of the start of Smailovic’s vigil, John McCutcheon began his 22-day tribute to a fellow musician, writing songs – 35, in fact – including more than a dozen than ended up on his 36th album, ‘22 Days,’ which was released late last year.

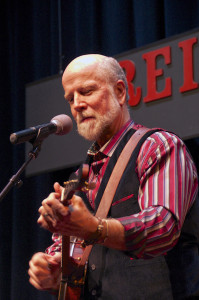

McCutcheon, an American master instrumentalist, song writer and folk musician who has carried on the traditions of Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie for more than 40 years, will perform June 28 at 9 p.m. at the Utah Arts Festival. His appearance on the Festival Stage coincides with the festival’s daylong celebration of the Intermountain Acoustic Music Association, which will have performers representing bluegrass, folk, Irish, American roots and Celtic music on eight performing stages. And, McCutcheon, along with musician and songwriter Kate MacLeod, will be the instructors for IAMA’s 7th annual Songwriter Academy, which will be held on the festival campus June 27 and 28.

His latest album underscores his gifts for musical storytelling, particularly as they capture moments that are simultaneously timeless and timely in how they represent both contemporary and historical events. Likewise, the music takes on an ecumenical flavor featuring, of course, his skills on the hammered dulcimer, along with accompanying musicians singing and playing, at various times, guitar, accordion, fiddle, banjo and bass. In ‘Forgotten,’ he honors Malala Yousafzai, the young teenage woman who was targeted by the Taliban because of her personal campaign for women education. The lyrics, against clean, pure musical lines, are: “We will remember/First day of school/Of each September/She is our daughter/She is our dream/She is our future/She is fourteen.”

His latest album underscores his gifts for musical storytelling, particularly as they capture moments that are simultaneously timeless and timely in how they represent both contemporary and historical events. Likewise, the music takes on an ecumenical flavor featuring, of course, his skills on the hammered dulcimer, along with accompanying musicians singing and playing, at various times, guitar, accordion, fiddle, banjo and bass. In ‘Forgotten,’ he honors Malala Yousafzai, the young teenage woman who was targeted by the Taliban because of her personal campaign for women education. The lyrics, against clean, pure musical lines, are: “We will remember/First day of school/Of each September/She is our daughter/She is our dream/She is our future/She is fourteen.”

In ‘Nothing Like You,’ McCutcheon’s lyrics tell the story of an undocumented worker who desires to have the dignity and respect that any individual deserves in a nation that has given many immigrants the chance to make their own American dream. They ring clear and unforgettable: “I am one in a million/We all look the same/A man with no papers/A man with no name/Just a good pair of hands/And a heart that is true/Willing to work/I am nothing like you.”

He also lightens the moment with songs that sparkle with the energy of a classic hootenanny. In the romping ‘Heaven’s Kitchen,’ which clips along marvelously in a shade over three minutes, McCutcheon sings praises to Southern cooking – rattling off the names of at least two dozen culinary staples, seasoning the mix with a chorus that proclaims, “Everybody gather ‘round and take your place/Bow your heads while we all say grace/Bless my soul, shut my mouth/Heaven’s kitchen comes straight from the South.”

Resoundingly impressive for someone, who up until his college days at a small school in northern Minnesota, had never been, as he explains in an interview with The Utah Review, “south of Milwaukee.”

One of the foremost musicians on the hammered dulcimer, McCutcheon made his first contact with the instrument in college when he met with some students who came from Arkansas and had in their possession a dulcimer, autoharp and a banjo – none of which any of them could play, he recalls. “They brought them along as reminders of home,” he explains, adding that it was then when he set out on his “crooked path to perdition – that is, learning to play the banjo in Minnesota – an ultimate sign of cultural denial.”

Shortly after, he set out on a three-month internship–which McCutcheon says “continues 42 years later”–in the Appalachians, his first experience in the U.S. South, where he found musicians to get the full feel for playing the dulcimer, fiddle, mandolin and all sorts of acoustic instruments. His passion expanded in many ways. A girlfriend who was in an instrument-building workshop gave him a handmade instrument as a birthday present. He found a mentor for the hammered dulcimer technique and performance in Paul Van Arsdale during the 1970s. They met when McCutcheon performed at a concert at the University of Buffalo. In fact, Arsdale, who is in his 90s and is nationally recognized as one of the nation’s greatest hammered dulcimer musicians, has played on several of McCutcheon’s albums. The Arsdale friendship proved helpful for McCutcheon in writing original compositions for the instrument. “Up until then, I would adapt Irish folk, ragtime and fiddle tunes for the dulcimer and soon I was able to write my own tunes,” he adds.

McCutcheon is prolific in his musical output, a direct result of his capacity to let patience guide his muse. There is a highly developed sense of perspective and context for the appropriate time in having a particular song appear for the first time in an album, collection or concert. He has an uncanny sense of conveying the most difficult of sentiments to articulate, especially after a tragedy involving mindless violence and death, such as the 2001 terrorist attacks. A prayer vigil in New York City inspired ‘Follow the light on home to me’: “Follow the light/When you’re lonely and lost/When out on the ocean/You are tumbled and tossed/Follow your heart/Wherever you may be/Follow the light on home to me.”

One of his most popular songs, ‘Christmas in the Trenches,’ was inspired by a backstage chat he had with an elderly woman in Birmingham, Alabama and which relates one of the most widely told stories in Europe from World War I. It is one of countless exquisitely simple yet powerfully effective examples of his story telling impact: “My name is Francis Tolliver, in Liverpool I dwell/Each Christmas come since World War I I’ve learned its lessons well/That the ones who call the shots won’t be among the dead and lame/And on each end of the rifle we’re the same.”

One of his most popular songs, ‘Christmas in the Trenches,’ was inspired by a backstage chat he had with an elderly woman in Birmingham, Alabama and which relates one of the most widely told stories in Europe from World War I. It is one of countless exquisitely simple yet powerfully effective examples of his story telling impact: “My name is Francis Tolliver, in Liverpool I dwell/Each Christmas come since World War I I’ve learned its lessons well/That the ones who call the shots won’t be among the dead and lame/And on each end of the rifle we’re the same.”

Raised a Catholic in the upper Midwest who later found a more suited spiritual home in the Quaker faith, McCutcheon was grateful for how his mother – who once worked as a social worker – encouraged him to be intellectually curious about the civil rights movement, in which the events of Selma, Montgomery, and Washington, D.C. unfolded before the eyes of a preteen boy. It wasn’t easy to always find the time. “My father was a traveling salesman and there were nine kids but she always took the time to answer my questions about what’s this stuff we were seeing on TV,” he recalls. The scenes made their lifelong imprint, as McCutcheon noticed there were many clergy involved in the civil rights movement. “More so than perhaps a radical professor, that religious language of faith and life was instilled in me and was filtered through the music that I wanted to see develop in provocative and illuminating ways,” he explains.

Music does seem to point a way out from becoming immobilized at death and tragedy. For ’22 Days,’ McCutcheon wanted to “honor my friend who chose to respond to violence and ugliness with a counterintuitive act of beauty,” echoing a 1958 quote by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.: “Don’t ever let anyone pull you so low as to hate them. We must use the weapon of love.”