In the first issue of Seven Arts, a cultural arts magazine launched in 1916, Romain Rolland, a French writer who was a close friend of Marcel Duchamp, contributed an essay titled America and the Arts. He paid great tribute to Walt Whitman – “the elemental Voice of a great pioneer,” the American corollary of Homer. Rolland envied the artistic opportunity of Americans who were born in “soil that is neither encumbered nor shut in by past spiritual eclipses.” He added: “Above all dare to see yourselves; to penetrate within yourselves – and to your very depths. Dare to see true. And then whatever you find, dare to speak it out as you have found it.”

Meanwhile, Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986), who was 29 at the time, was opening her first show as an artist. In 1915, during her spare time when she was not teaching art at a South Carolina college, she had begun a series of abstract drawings in charcoal that drew the interest of Alfred Stieglitz in New York City, the owner of 291, an avant-garde art gallery, who would later become her husband. O’Keeffe epitomized the ideal Rolland had set forth in his essay.

In January 1939, in an artistic statement for a new exhibition, she explained her unquenchable creative passion for painting the New Mexico high desert. She never felt that she had spent enough time in the desert so to satisfy her desire she brought home the bleached bones she found every time she went. She explained, “The bones seem to cut sharply to the center of something that is keenly alive on the desert even tho’ it is vast and empty and untouchable – and knows no kindness with all its beauty.”

In the high desert landscapes of Utah, Cody Chamberlain has found his own obsessive muse and his spiritual solace. In his artistic statement, he writes, “I do not fool myself into thinking I can conquer the wilderness. I am a willing subject to it. I believe we are all subjects to it. I want my art to reveal the beauty of this land I have come to know so well, to help people realize they are a part of this ecosystem and that they will benefit from nurturing it.”

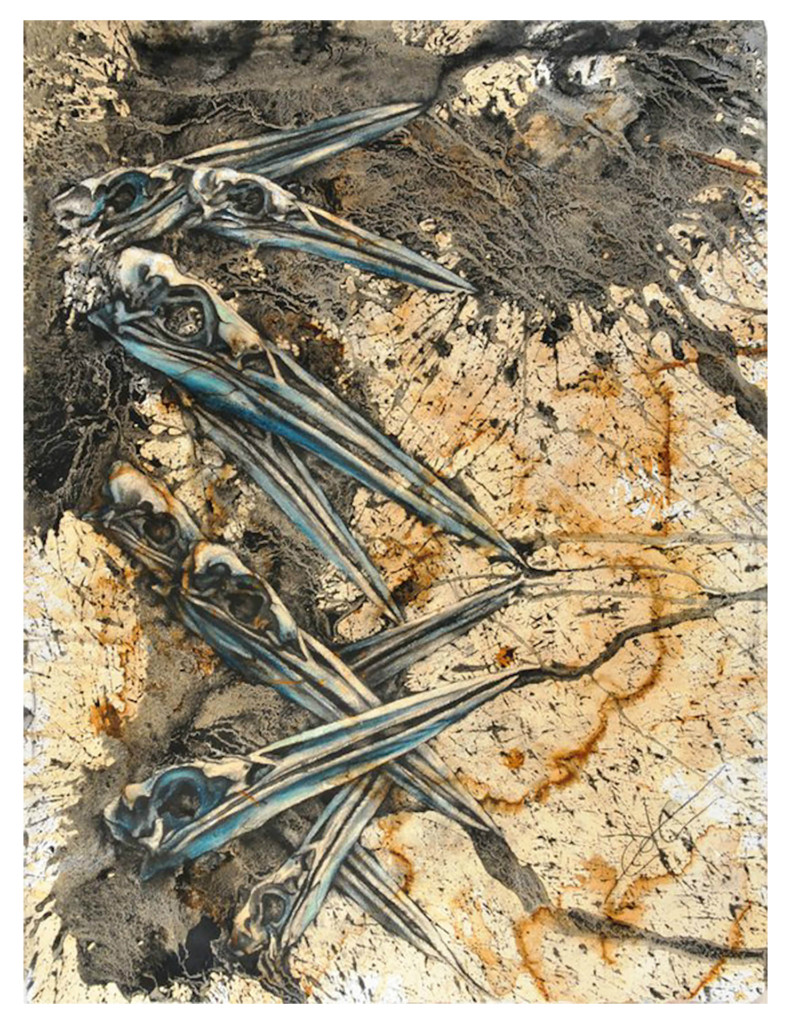

During his interview with The Utah Review just a few days before Thanksgiving, Chamberlain, who has worked with the U.S. Forest Service but now works full-time as an artist, made clear how his love for the desert always is too strong and urgent to resist beyond a short respite. Soon, he returned to the desert, taking advantage of the sunny, unusually warm, days that marked this year’s late November. Two days after Thanksgiving, his Facebook page percolated with his latest discoveries in the Utah desert – junipers, a “spectacular” kit fox skeleton spotted in dunes, for example. He was thrilled to find his inspiration for the next work in his Bird of Prey series. With the guidance of HawkWatch International, he captured photos of a Great Horned Owl, which would provide the essential reference for his next painting.

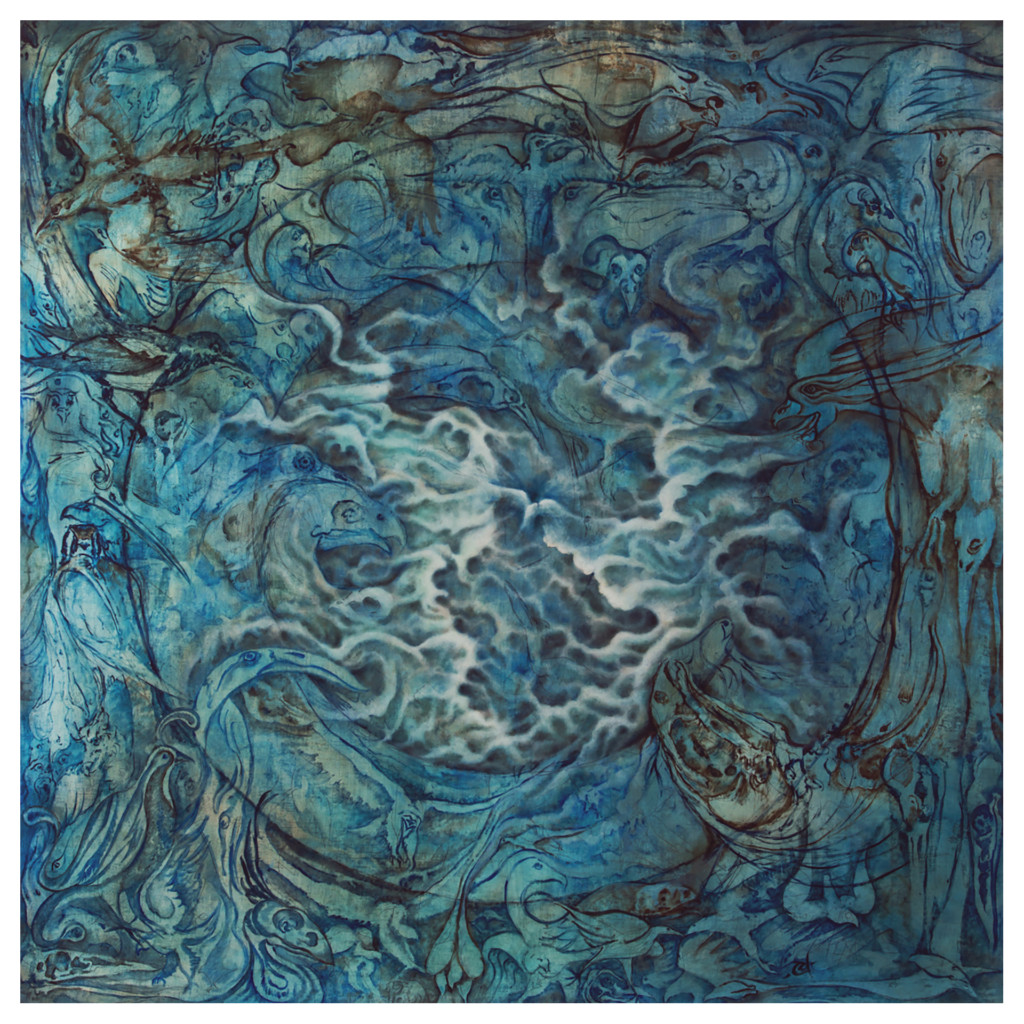

A week prior, Chamberlain had returned from a trip to the eastern U.S. visiting museums and galleries as well as places of nature. The best advice for any aspiring writer is to read as much as possible. Likewise, conscientious artists constantly are in a similar conditioning mode. Chamberlain was thrilled to see works by O’Keeffe, Salvador Dali, Max Ernst and others. Upon his return, he attended the opening reception of The Statewide Annual competitive exhibition, coordinated by the Utah Division of Arts and Museums, where one of his works is on display at the Rio Gallery in downtown Salt Lake City. Chamberlain is one of 69 artists who was selected to participate in the juried show, which includes 500 works of art in various media and were selected from a record number of submissions. The oil painting selected for the show is from his Bird of Prey series, measuring 48″ by 48″. He also was in the 2016 show.

Chamberlain’s visibility as an artist is flourishing. This includes works in two exhibitions this year at the Springville Museum of Art, the Eccles Community Art Center, Logan Fine Arts Gallery and a solo show at Sundance Studio in 2016. He also was one of the artists selected last year for the Finch Lane Gallery’s Artists of Utah 35×35 Exhibition.

Like so many artists in the latest creative wave of the Utah Enlightenment, Chamberlain focuses on a representation of the formidable realities encompassed in the New American West creative body of expression. It’s a rapidly expanding and representative catalog of what is at stake or what could be lost if we refuse to be responsible, ethical stewards of the land and the spectrum of all its natural elements. Chamberlain’s work is daring without the necessity of being explicit, politically or ideologically.

He earned his bachelor of fine arts degree in painting at Utah Valley University and he has pursued studies in anthropology and archaeology at the master’s degree level at The University of Utah. However, Chamberlain has opened the intellectual possibilities of his creative expression much in the same way that O’Keeffe was inspired by one of her teachers, Arthur Wesley Dow. An American painter born in the 19th century, Dow published a highly regarded 1899 text on art composition, which admonished artists who focused too intensely on realistic representations of nature.

It is no surprise then to learn how Chamberlain has immersed himself in the creative canon of the New American West to liberate his experience – to blend completely the lines dividing the practicalities of life and the compulsion to create art. And, to “fill a space in a beautiful way,” as O’Keeffe famously interpreted Dow’s unprecedented rule of instruction.

“I didn’t want to be an art teacher,” Chamberlain explains, “and I realized how important it is to be prolific so that’s is why I decided to go full-time with my art.” His living space is cramped with works and sketches. He quickly and regularly fills up his smartphone’s storage capacity with photographic images – as many as 20,000 at a time – that become references for creating his work.

Chamberlain’s intellectual underpinnings inform his creative process, which seems to move quickly and effortlessly. He is comfortable working on four or five pieces at a time, of various sizes. His intellectual diet is balanced with a diverse palette of works from artists, authors, poets and musicians: Wallace Stegner, Ansel Adams, Edward Abbey and Cormac McCarthy, to name a few. Bob Dylan’s Dirt Road Blues from the 1997 album Time Out of Mind is an intriguing choice for Chamberlain. The music is a pretty conventional up-tempo blues signature motif but the lyrics are something else:

I’ve been at my shadow

I been watchin’ the colors up above

Lookin’ at my shadow

Watchin’ the colors up above

Rolling through the rain and hail

Lookin’ for the sunny side of love.

Gonna walk on that dirt road…

The Dylan song explains how Chamberlain’s obsession with Utah’s landscape — its deserts and mountains — takes full control in his creative enterprise. Leave the desert or the mountains temporarily but it is nature, not man, that relentlessly reminds who really is in charge — even when he is back in the city or lower elevations.

In one Facebook post, Chamberlain quotes from Aldous Huxley’s Texts and Pretexts, published in 1932: “The poet is, etymologically, the maker. … Experience is not what happens to a man; it is what a man does with what happens to him. It is a gift for dealing with the accidents of existence, not the accidents themselves. By a happy dispensation of nature, the poet generally possesses the gift of experience in conjunction with that of expression.”

The Huxley quote illuminates his inner creative impetus. For artists like Chamberlain, they augment what scientists, naturalists, environmentalists, historians and authors provide and offer with wisdom and expertise when they are discussing the American West. Chamberlain aspires to the same sort of catholic, cosmopolitan, intellectual independence that distinguished Huxley’s work and standing in the cultural cosmos. Chamberlain does not select beautiful specimens of the desert and its natural elements necessarily for purposefully attempting to illustrate a particular ideology or philosophy but rather to express his own attitudes, feelings and emotions in a way that confidently elevates and amplifies an unspoken yet familiar soulful connection for so many people, even if they have never visited a Utah desert landscape. Take note, though: Chamberlain says he is more than happy to have people join him on any of his visits to the desert.

For more information about his work, see Chamberlain’s website.

The Statewide Annual exhibition is open to the public until Jan. 12.