NOVA Chamber Music Series’ 46th season is all about personality, as noted previously in The Utah Review. The eight concerts for the 2023-24 season will showcase a generous sampling of the outstanding level of musicianship that exemplifies just how high the bar of artistic quality has been set in Utah. The Utah Review offers a closer look at a few musicians who are slated to perform this season.

ALEXANDER AND AUBREY WOODS

To riff off the standard opening of The Odd Couple television series from the 1970s, can two violinists live together without driving each other crazy? Violinists are occasionally known to be ambitious competitors or friendly adversaries and sometimes peer criticism can sting: for example, “um, that was a bit out of tune,” or “stop playing too loud.” But there also are fine examples of violinists married to each other who have thriving careers, including Gil Shaham and Adele Anthony or Ilya and Olga Dubossarskaya Kaler.

The NOVA Chamber Music Series already has a couple of prominent examples of husband-and-wife musicians who do as splendidly on stage as they manage in their family home lives: pianists Jason Hardink and Kimi Kawashima and Utah Symphony violist Brant Bayless and Fry Street Quartet cellist Anne Francis Bayless.

For violinists Alex and Aubrey Woods, love came like a lightning strike. When Alex was a candidate for the violin faculty who later would establish and direct the BYU Baroque Ensemble at Brigham Young University, Aubrey’s brilliant playing as a student in a master class he led struck him immediately. In an interview, regarding how quickly their relationship blossomed, Alex says that “we made sure that everything was appropriate.”

Everything moved quickly. “In the fall semester, Aubrey switched teachers, we were engaged and were married next semester [March 2011],” he says. Aubrey echoes her husband’s words about making sure appearances were as proper as possible, adding that “it was a bit tricky at first because we knew that violinists have a reputation for being competitive so we were both committed to figuring this out.”

He had studied with some of the titans on the concert stage including Pinchas Zukerman, Itzhak Perlman, Syoko Aki and Mark Rush. He came to BYU with credentials representing two widely distanced points on the musical spectrum: a well-known performer in early and Baroque music on period instruments and an equally strong portfolio in contemporary music representing composers such as John Adams, Alvin Lucier, John Zorn, Tod Machover, Ingram Marshall and Tarik O’ Reagan.

Meanwhile, Aubrey was still figuring out what a career as a professional violinist could become. Her family had music running deep in their veins. Her father, Christian Smith, was a bassoonist and teacher who became one of the first musicians to join the Orchestra at Temple Square, which the late Gordon Hinckley, then president of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, gave the greenlight to establish.

Aubrey’s diligence as a violin student paid dividends quickly. At 15, she joined her father in the orchestra. Later on, her husband would become a member as well and then a sister (Danielle) who was a horn player. “I was the oldest of nine kids and so I figured the best way to escape the chaos at home was to keep practicing,” Aubrey recalls.

It didn’t take long after graduation — which was just one-and-a-half years after the Woods were married — for Aubrey to make her own mark as a career violinist. In her first professional audition, she landed the post of concertmaster of the Ballet West Orchestra. Joining her husband, she mastered the technical challenges and unique sound of the baroque violin and would later perform with period instrumental ensembles including New York Baroque Incorporated, the Sebastians and Musical Angelica Baroque Orchestra in Los Angeles.

Their marriage has produced all sorts of reciprocating musical discoveries for them, individually and collectively. The Woods, who will be the featured artists on the second Gallery Series concert, which will be the final concert of NOVA’s 2023-24 season next May, make the point. The concert features selections from the Big Three of the Baroque Era to be performed on period instruments: Bach, Handel and Vivaldi. There also is Stravinsky’s Suite Italienne, a 1933 work for piano and violin. The final work is Kenji Bunch’s Apocryphal Dances, for string quartet and which premiered in 2017. Described as a love letter to the old style dance music composed in the 18th and 19th centuries, the work nevertheless has the contemporary harmonic language that adds the proper bite in this homage to an earlier period.

Both say that they have been influenced by each other’s playing style. Aubrey tends to be on the back of the beat while Alex is on the front of the beat. “When I worked with Perlman, I remember him saying how difficult it was to find somebody who would tell him the truth about how he really sounded,” Alex explains. “Aubrey and I totally trust each other and it has become a huge advantage in how to handle tricky moments in critiquing because we are willing to do it in a respectful and tactful way.”

That May 2024 NOVA concert will be a unique treat for Salt Lake City audiences. The Woods make the case for how playing baroque music on period instruments can produce a distinctive soothing, deeply spiritual significance in the listening experience. “Period playing is really important and prevalent in big city centers, which have become thriving early music scenes,” Alex notes.

Baroque music’s renaissance in the 20th and 21st centuries, in particular, has produced an invigorating fresh appreciation about a genre that was once perceived as aloof, emotionally deprived and standoffish, especially if one listens to the music which was recorded in a sterile, overproduced environment. Indeed, there is an admirable wabi-sabi dynamic about playing Baroque music on period instruments in live performance. “I really love the trade offs,” Alex says. “Sometimes, the strings squawk or some notes might be out of tune.” But, then there is the facility of the Baroque bow, when compared to the Tourte bow that became the foundation of modern violin technique.

The Baroque bow is typically about two to four inches shorter than a modern bow, weighs about 10% less and the stick curves a bit outward from the hair of the bow, which is typically loose at the frog. The Baroque bow was designed to make the violin emulate human dimensions of the voice. Violinists also held the bow well above the frog, unlike modern bows where the player holds it at the frog.

Baroque era concerts were almost always filled with new music. The idea of performing music composed a few short decades earlier was not a common practice. As for players on period instruments, Alex is reminded by what Robert Mealy, a Yale professor who is among the most prominent authorities about the Baroque violin, says that unlike its modern successor, the Baroque instrument was made to play in three fingerboard positions: “first, third and emergency.”

Aubrey says that she tells students learning to play on a Baroque violin is “teaching us to relax,” especially because the player does not need to use a chin or shoulder rest.

Music is part of the Woods household, with four boys under the age of 10. The boys’ first names are a tribute to The Beatles (with the exception being Rex instead of Ringo). Their two oldest boys are already studying piano and their four-year-old has been “begging for a piano lesson,” Aubrey says. They tried violin a few years ago but piano has stuck with them, something that their parents are more than happy to accommodate.

Apparently, the boys love it. They practice 45 minutes before their school day begins. “To keep the joy, I make sure they have different methods books,” Aubrey says. YouTube videos have inspired learning to play guitar and one is learning to play covers of Beatles songs on the ukulele. And, for the young musician who is just as or even more obsessed with Legos, Aubrey and Alex know how to negotiate the deal about practicing without causing any or as little drama as possible. Nevertheless, the Woods are pleased to see their sons so willing to learn how to speak the language of music at home, which both say is no different from learning a different tongue or dialect from another country.

THOMAS GLENN

Like many other musicians who will be on the NOVA concert slate this season, tenor Thomas Glenn is comfortable with diverse points on the spectrum of music history. In his operatic career, he has been known for roles from several warhorse operas by Rossini (Il barbiere die Siviglia and L’italiana in Algerì) and Mozart (Così fan tutte), as well as the role of The Evangelist in Bach’s St. Matthew Passion.

Just as prominent has been his collaboration on works by contemporary composers. In 2012, Glenn and Sasha Cooke accepted the Grammy Award for Best Opera Recording, which was given to John Adams’ Doctor Atomic (where Glenn created the role of Robert Wilson). For NOVA this season, Glenn, a member of the Utah State University faculty as area coordinator and assistant professor of voice, will appear twice: on the April 14, 2024 Libby Gardner Hall Series concert, performing the Utah premiere of a new work by Akshaya Avril Tucker, scored for the Fry Street Quartet and tenor, as part of Gabriela Lena Frank Creative Academy of Music’s Composing Earth cohort and the March 24,2024 Gallery Series concert performing Britten’s Canticle III: Still Falls the Rain.

Glenn’s connections to Utah are a bit like a game of ping pong. “I was born in Provo: a BYU baby,” he says in an interview with The Utah Review. When he was three months old, his father (a Canadian from the province of Alberta) and his mother (a California native) moved to Calgary.

In his teen years, he would return to Utah for his undergraduate studies at BYU. Afterward, he went on to earn his master’s and doctoral degrees, respectively, at the University of Michigan and Florida State University. His international career taking shape, he landed a spot with the San Francisco Opera as an Adler Fellow, where he would most notably take on the Doctor Atomic role of Robert Wilson, the youngest group leader at the Los Alamos laboratories who worked and challenged Robert Oppenheimer and Enrico Fermi.

Proving once again how tightly woven the musician’s networking world can be even without colleagues immediately recognizing it, Glenn and Robert Waters, Fry Street Quartet’s first violinist, were surprised to discover years later that Waters was playing in the San Francisco Opera pit orchestra at the same time when Glenn sang on stage. ”We both thought how incredible it was that we never met during that time,” Glenn recalls.

With the rapid expansion of social media apps being launched in the tech-intense Bay Area during the early 2010s, Glenn and his expanding family — first the birth of twins and then two more boys — decided that the area had become too expensive so the family relocated to Calgary.

Throughout the remainder of the 2010s, Glenn stepped a bit back from the interpretive creative endeavors as a musician. At the time, he did not think about coming back to academia. He went to law school in Canada for about a year and a half but he realized that the only way he could manage paying the bills would be to land substantial musical gigs. “Up to this point, my career had been heavy in the creative and interpretive sides of reasoning but the other side of my brain also craved activities for logic,” he explains.

He enrolled in a software engineering boot camp to become a coder. But, he came up short in finding jobs that appealed to him. One offer was to be a customer service consultant for data management, working between 8 p.m. and 8 a.m. for an employer that was based in India. Then, he decided to scout out teaching jobs in Alberta and he made his first connections with Utah State University in 2013 and 2016. The school already was willing to create a position for him.

“The sanest thing to do was to come to USU,” he explains, but he also wanted to make sure that he was ready to settle into an active academic role. Glenn says that he thought about students being motivated enough to put in the effort and time to practice. And, while he was interested in the opportunity to shape the pedagogy of voice toward a vision he believed would resonate, he also was aware of the challenges of advancing through the hurdles of a rigorous tenure and promotion process.

While his performing engagements have taken him around the world, Glenn looks back to the days in the 2000s when he stepped from apprentice into the spotlight as Wilson, the significant dissenting character, in Doctor Atomic, which featured the libretto by Peter Sellars. “Others had shrugged off the role but I was freaking out about the opportunity,” he says. “I already had considered Nixon in China [another hugely successful Adams opera] as the defining American opera of our times.” In San Francisco, he enjoyed the roles of the Steersman in Der Fliegende Holländer, Vitek in Janacek’s The Makropulos Case and Gherardo in Puccini’s Gianni Schicchi.

Ironically, it was the small but serendipitous role that Mozart’s The Magic Flute factored unexpectedly in the consequential switch of tenors for the Adams opera. Tom Randle had been slated to premiere the Wilson role in Doctor Atomic but he had to fly to London for the filmed production of the Mozart opera, which was directed by Kenneth Branagh. “I stepped into rehearsal and Sellars liked my performance and told me that he wanted to find a way to put me on stage,” Glenn says. “I didn’t realize at the time how serious he was. At the second to the last dress rehearsal, he told me that I was replacing Tom Randle.” It became a defining role in his portfolio, which already had been fed nicely by Donizetti, Mozart and Rossini operas and the bel canto tradition.

In his review of the Doctor Atomic premiere, music critic Tim Page at The Washington Post wrote, “Thomas Glenn, as the dissenting physicist Robert Wilson, easily negotiated crushingly difficult music in a high, boyish tenor. (An officially designated Rebel With a Cause, he wore an open shirt, as opposed to the dark suits of Oppenheimer and Teller — such is symbolism.)”

Glenn studied voice and piano into his teen years but eventually, as he describes it, “voice slaughtered piano.” However, Glenn appreciated jazz piano and when he was fourteen and fifteen, he would scour the library stacks for recordings by artists such as Keith Jarrett and Chick Corea and transcribe them. “It gave my ear more leverage for encountering new music,” he says, adding that while others could vehemently dislike Schönberg or composers of the Second Viennese School, he had a voracious appetite for their music.

At USU, Glenn says he feels sometimes like a preacher preparing students to appreciate and engage the context of new music. “Teaching voice is one thing to get the techniques in the tool belt but there also are challenges of updating older works and making them palatable for a modern audience,” he explains. “But, it’s also creating new music in an age where people of all ages are looking at politics and the world’s problems in many different ways.”

One major addition to the curriculum at USU is that learning the art of composition will be required of all voice students. “I ask voice students who have been working to master works of the last 400 years written by non-singers if they are okay with that,” he says. “At a certain level, I am not sure how composers can understand the voice in the same way that professional singers comprehend what their voices can do.” He sees value in the university setting, by encouraging singers to compose for their own instrument.

Glenn says he is excited about his upcoming performances in the NOVA season, including the opportunity to sing a new work, accompanied by the Fry Street Quartet. He also shares the group’s deep appreciation of Benjamin Britten’s music and the assessment of the British composer as one of the world’s greatest in the last century. This includes the operas Billy Budd and Turn of the Screw, other song settings including Canticle II: Abraham and Isaac and the Utah Festival Opera and Musical Theatre’s recent presentation of Britten’s War Requiem. Of Canticle III, Glenn praises its extraordinary opening in its stillness and sustained notes that put the audience into the proper captivating state for anticipating how the tenor comes elegantly into the composition.

ERIN SVOBODA-SCOTT

Erin Svoboda-Scott has been a familiar presence on the NOVA stage. The associate principal for clarinet in the Utah Symphony has a prolific portfolio as soloist and chamber ensemble musician. Her credits include a premiere of Michael Gandolfi’s Concerto for Clarinet and Bassoon with her father, Richard Svoboda, who plays the bassoon.

When she was five, Svoboda-Scott started on piano. In an interview, she says, “piano was a good start but then I started taking clarinet lessons [at the age of nine] so I could play in band when I was in middle school. But by high school, I had to pick one instrument over the over because both were competing for my time so clarinet was the obvious choice.” She adds that her smallish hands did not make it any easier to play sweeping pieces like Rachmaninoff etudes.

As much as she enjoyed playing school band arrangements of music from films such as Jurassic Park, she considered the opportunity to play more classical things in orchestras a dream job. Like many young musicians who are more than happy to show off their newly acquired skills of playing flashy works with impressive passages of fast notes, Svoboda-Scott at the time enjoyed clarinet showpieces by Carl Maria von Weber, Carl Nielsen and others.

For a clarinet player in youth orchestra, a time she remembers very fondly, there was a bountiful feast of music to highlight the instrument, such as Mahler’s symphonies, Richard Strauss’ Ein Heldenleben and orchestral warhorses such as Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony.

Her studies took her to the New England Conservatory of Music, Temple University and Manhattan School of Music where she studied with some of the nation’s elite clarinetists — Thomas Martin of the Boston Symphony, Ricardo Morales of the Philadelphia Orchestra and Mark Nuccio of the New York Philharmonic and Houston Symphony, respectively. Summers were packed with music festival gigs including Tanglewood, Marlboro, Pacific and Aspen.

In youth orchestra, there were some opportunities to play contemporary music but they often were works that were “not incredibly out there as new expressions,” she recalls. But, the summer music festivals offered solid opportunities to explore new music, such as Tanglewood where she first encountered Bright Sheng’s Concertino for Clarinet and String Quartet. (A side note: Sheng’s Hot Pepper (2010), scored for violin and marimba, will be featured on NOVA’s Jan. 21 concert). Other cherished chamber music pieces in her repertoire include Brahms’ Clarinet Quintet in B minor, Op. 115, and Béla Bartók’s Contrasts for clarinet, violin and piano.

As for her appearances in the upcoming NOVA season, Svoboda-Scott looks forward to the opening concert’s performance of György Ligeti’s Six Bagatelles, which is scored for woodwind quintet featuring members of Utah Symphony winds sections. Composed during the time when the Communist regime in Hungary censored the composer’s music, this transcribed set is a jaunty and rollicking interpretation of the country’s folk music roots. She also will be joined by violist Yuan Qi and pianist Cahill Smith on György Kurtág’s Hommage a Robert Schumann, which pays tribute to Schumann’s flair for suites of short fantasy pieces.

Next month, she will participate in the Utah premiere of Lullaby for the Transient (2018) by Michi Wiancko, which is scored for string quartet and clarinet. Wiancko was commissioned by the Aizuri Quartet to write the piece, which had premieres at LiveConnections in Philadelphia and at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in NYC, on consecutive days five years ago. Svoboda-Scott adds that the parts for the work include the full score, which she says is helpful given that each instrumentalist’s role depends so intricately upon what everyone in the ensemble is doing at a specific moment.

Svoboda-Scott says that she appreciates how open and trusting NOVA audiences are for contemporary music, which include world and Utah premieres every season. “I’m always happy to see that NOVA email requesting if I am available to play on an upcoming work,” she adds.

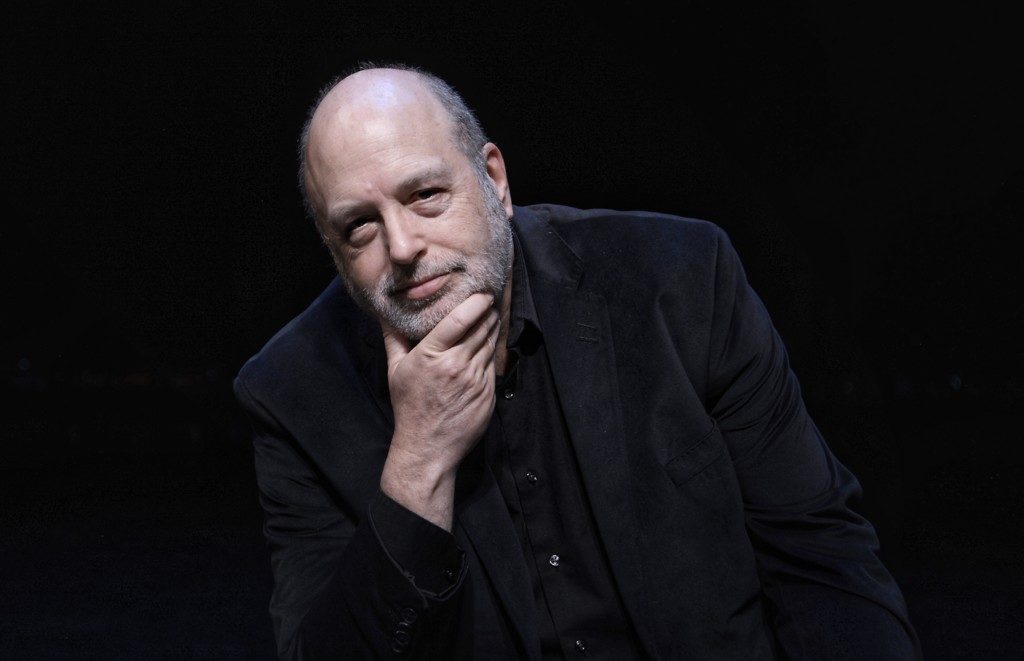

FRANK WEINSTOCK

When Frank Weinstock retired in 2011 after a long distinguished career at the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music and came to Utah with his wife, Jannell, who had retired after serving as vice president and general manager of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, it was the Beehive State’s valuable acquisition of a legend in the piano world.

Weinstock’s legacy as a performer and as a teacher stretches across every continent (save for Antarctica). Among the many accolades are some interesting side bits: for example,an accomplished music-software engineer, his work Home Concert Xtreme was awarded the 2010 Frances Clark Keyboard Pedagogy Award as the outstanding keyboard-pedagogy publication in that year.

Weinstock has been featured numerous times on NOVA’s concert stage in recent seasons, particularly in the canon of classical Viennese chamber music ensemble masterpieces. “I wish I was competent in new music,” he says in an interview, adding that nonetheless, he enjoys the lively local scene for contemporary works and considers pianists such as Jason Hardink and others who have performed them, without peer.

Weinstock was raised in a household of musicians who also played recordings of works by Beethoven, Brahms and Schubert. As concerto soloist, he has appeared with many conductors including Jesús López-Cobos, Erich Kunzel, Keith Lockhart, Jorge Mester, Gunther Schuller, Markand Thakar, and Luthero Rodrigues.

But, he considers chamber music to be the most satisfying of all performing genres. Weinstock, for instance, has performed with the Tokyo and American String Quartets, Leonard Rose, Larry Combs, Glen Dicterow, the Percussion Group Cincinnati, and with members of the Guarneri, LaSalle, Manhattan, and Berkshire Quartets. “In chamber music when everything feels right, it is really fantastic and more satisfying than just about anything else in music,” he says.

Among his most memorable recent performances with NOVA, he cites last year’s offering of Brahms’ Clarinet Trio in A minor, op. 114., with Svoboda-Scott on clarinet and Anne Francis Bayless on cello. Another was a 2019 performance of Bartók’s Contrasts, again with Svoboda-Scott on clarinet and Alexander Woods on violin. Just these two examples highlight the consistent excellence of the critical mass in chamber music ensembles on the local scene and how well integrated the musician’s ecosystem is in Utah.

Weinstock says when it comes to pianists, Utah’s culture is thriving. For more than two decades, the state has been cited as having more pianos per capita than any other in the country, and it has a comparably high ratio of piano technicians and dealers to anchor the market. And while not all of them will land in a professional career, Utah has more piano students per capita than any other state. And, of course, Salt Lake City is home to the Gina Bachauer International Piano Foundation, where Weinstock also has served as juror for the artists competition that brings young pianists from around the world.

A native of Oberlin, Ohio, Weinstock studied at the Oberlin and New England conservatories of music. In his retirement, he has spent time on finessing his performing repertoire and, in particular. has turned to the exceptional output of piano works by Schubert. Among them are the last three piano sonatas the composer wrote in the final months of his life before he died at the age of 31 in 1828.

He will perform Schubert’s Piano Sonata in A Major, D. 959 on the March 24, 2024 Gallery Series concert, featuring the music of Britten and Schubert. The work teems with pastoral, playful and nostalgic moments, such as those found in Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony. The Andantino movement has the capacity for an ethereal eeriness that only Schubert could have fashioned.

Weinstock says that each of the final three Schubert sonatas is “a world unto itself but when they are put together they make a wonderful universe representing every imaginable emotional state.” He is particularly struck by how the theme of the last movement of the sonata he will play at the concert brings back a theme from a much earlier piano sonata Schubert wrote when he was 20 (Piano Sonata in A minor, D. 537). “It is amazing how it must have stuck with him because when he brought it back from his less mature work, he smoothed out what already was a gorgeous theme into something memorable and extraordinary,” he explains.