EDITOR’S NOTE: Ballet West is celebrating its 60th anniversary and the newest production, which opens Nov. 3, is a tribute to Willam F. Christensen, who co-founded the company. Featured are Christensen’s version of The Firebird, the world premiere of Fever Dream by Joshua Whitehead, recently retired and long-term Ballet West artist, and George Balanchine’s Stars and Stripes. For tickets and more information, see the Ballet West website.

INTRODUCTION

As The Utah Review has frequently cited, Utah’s dance community has long worn the empress crown in the performing arts. When Willam Farr Christensen (more familiarly known and loved as Mr. C) and Mrs. Glenn Walker Wallace co-founded Ballet West 60 years ago, the vision of Utah having its own ballet company and school crystallized rapidly, and within its first decade, it became the largest ballet company in one of the smallest metropolitan areas in the country. That distinction is just as clear today. In a recent Dance Data Project interview, current artistic director Adam Sklute said, “It is truly amazing that a company with a budget that now puts us in the top 10 companies in America serves the smallest population of America’s top 40 companies. It really speaks to our communities, and state’s love of arts and culture. Our theater seats about 1,700 people and we are able to sustain seven programs a year with approximately 30 Nutcrackers, eight to ten shows of our big full-lengths, and five of each of our mixed repertory programs with well-sold to full houses.”

Introducing her 1979 tribute on KBYU-FM to Mr. C., a year after he retired from the company he founded, Ruth Draper of the Utah Arts Council set the tone:

Major foundations and corporations have been willing to assist dance because of Mr. C. And once that awareness and support for dance was begun it snowballed to the point of making Utah a mini-dance capital. Outside New York, Utah has more dance per capita than any other state. And that dance began here, and will continue here: largely through one man’s effort…

The full story behind Ballet West starts more than 120 years ago in Brigham City, Utah. Some of the early chapters in this story took Mr. C and his two brothers, Harold and Lew, to New York City, Chicago, Cleveland, and many other stops on the Orpheum Circuit at the height of the Vaudeville Era. The Christensen brothers received training in ballet from European masters who came to the U.S. during the greatest periods of immigration that the nation witnessed. Other stops include Portland and San Francisco, where Mr. C, who later would be joined by his brothers in making the American West just as essential a cultural center for ballet as the East Coast. Finally, Mr. C would return to Salt Lake City in 1951 to make American ballet history at The University of Utah, which paved the remainder of the path leading to the 1963 founding of Ballet West.

In Ballet West, Mr. C saw it as stimulating and inspiring the nobility of humans through dance. In a 1983 interview, he said, “I like to quote Anna Pavlova… where man walked on the street as man; and peasant and ‘peasant is more earthy. And as the classical ballet is as noble as man would like to be … hopes to be … dreams to be.”

EARLY YEARS IN BRIGHAM CITY

Mr. C was born in Brigham City, Utah in 1902. With brothers Harold, who was born in 1904, and Lew, born in 1909, they were part of the family’s third generation in Utah, which included four boys and two girls in their household. An older brother (Gus) was not interested in pursuing dance. The first Christensens who converted to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints in Denmark came to Utah in 1854, just seven years after the first LDS settlers arrived in Salt Lake City.

Everyone in the family was a musician. His grandfather Lars was a fiddler, not a violinist, as Mr. C described him. The young brothers learned Danish folk dances but, as he recalled, “We didn’t like it, my brothers and I, particularly, because we liked to play around, and little boys don’t like to dance with little girls. When we got older the pattern changed. But I was raised with the violin and the piano. My father was a violinist, my uncle’s a violinist and some played the clarinet, the flute, different instruments.” The family bands scored and arranged their own music and from 1893 to 1905, they played at Saltair.

Mr. C. played piano, percussion and drums and horns in the band but he became fascinated with ballet dancers. At the age of 10, Mr. C. started studying with his uncle Lars Peter Christensen at the Christensen Academy of Dance and Music in Brigham City. In a 1979 interview with KBYU public television, he recalled how he decided to switch from being a musician to a dancer: “And when I saw those girls dance in their little ballet exercises, (I was pretty young), they looked much better than the piano to me.” Two other uncles (Moses and Fredrick) left Utah to open dance schools in Portland and Seattle.

In his earliest performing days which took him out of Utah, Mr. C would come back to Utah often because he was short on cash. He would take advantage of the recitals which his uncle’s school offered. Salt Lake City also had a well-known opera singer at the time Emma Lucy Gates Bowen, who founded the Lucy Gates Grand Opera Company in Salt Lake City in 1915 with her brother. who conducted the performances. Their repertoire included La Traviata, Faust, Carmen and Romeo and Juliet. Mr C and Lew would dance in operas that the company performed.

Eventually, Mr. C organized a little professional group in Los Angeles. “And I don’t think … we were good dancers, but we didn’t understand theater very well,” he said in his 1979 KBYU interview. “And the only thing at that time were dancing in movie theaters.”

TRANSITIONS EASTWARD AND VAUDEVILLE

In the 1920s, Mr. C traveled to Chicago and then to New York. There were no ballet companies in U.S. at the time but there were small ballet ensembles. With brothers Lew and Harold, Mr. C branded themselves as The Le Christ Brothers, who worked the Orpheum Circuit in the 1920s.

On the same bill when they played The Palace in New York City was the legendary comedian W.C. Fields. “We did a group, what we call Adagio, where we dance with the girls and then the girls did individual variations (solos),” Mr. C recalled. He and brother Lew would do solos of their own and then the four did a finale.

One of the most famous venues the group performed early in their career was at the Hippodrome in the Big Apple. “You could say we were odd balls. They called us ‘Dancers Extra-Ordinary’ And in New York City there were people who understood ballet to a degree,” Mr. C explained in the KBYU interview. “And so, we were accepted, because we couldn’t do more like we do now in ballet companies – pay more attention to the script or the score. You had to do sensational things: lots of turns, lots of jumps, tours on lair, lifting girls, lift them over your head…I remember one time, [at] the Radio Keith Orpheum, they had a designer who made beautiful costumes and we had harlequin tights.”

When Verdoia asked Mr. C how he choreographed the group “so that the guy 12 rows back with the tomato in his pocket wouldn’t throw it at the stage?” He responded, “I would do circles, going lickety cut around and coupe jetes and little turning in the middle, and we would have to do beats and lift the girls nicely.” If the audience applauded, they would do more “elegant things.” He added, “If we’d missed the first hand, then you’d fight like hell for the second hand. Sometimes the comic wouldn’t do well. If we did very well, he had to work hard.”

Mr. C formed a quartet (The Mascagno Four ) and his father (Christian) went along as conductor. They did straight ballet, using music of Strauss and Delibes. “It was a little highbrow for the general theaters, but it was good for us,” Mr. C said in 1979. It was during those performing years when Mr. C met his first wife, Mignon Lee, who became part of the troupe.

However, once the group left New York City and ended up in places such as Cleveland, Ohio, it was a different reception. “If we came out in tights, they thought maybe we were acrobats or tumblers,” Mr. C said. “We sensed it. So my brother and I put on the dark pants with a sash and opened shirt and the girls in a nice tutu length dress and then we got a big reception.”

In his KBYU interview in 1979, the memories of those performing days in the 1920s were still vivid in Mr. C’s mind. In Keokuk, Iowa, he recalled watching the stage manager and theater manager talking about them:

The stage manager said, ‘You know, the manager doesn’t know exactly what you do. He thought it was some of a fling.” And he said, “‘And I told him it was some sort of Adagio’ – you know, where you carry the girls.’ So I said, ‘Well, you’re both a little bit right, it’s ballet. But we do lift the girls, and all these various things we do.’ So we were very early for that type of entertainment.

Looking back on the experience, Mr. C grounded the realities of it for his KBYU interview: “Being raised in a family with music and dance and opera, I couldn’t quite understand why they couldn’t understand what we were doing. We didn’t try to be an innovator. We were an innovator, but we didn’t try. That wasn’t in our mind. Our mind was trying to perform; do the things we were trained in and make a living at it.”

Verdoia’s Insight program in 1987 nicely summarized how vaudeville played a profound formative role in the artistic lives of Mr. C and his two brothers:

The Christensens had to hand carve their own place in American dance through the only vehicle available at the time– vaudeville. First, as the LeChrist Brothers, Bill, Harold and Lew Christensen danced the boards of a hundred vaudeville houses coast to coast in a never-ending stream of whistle stop towns and big cities. To grab an audience that could snore at the mere mention of the word ballet, the brothers drew upon an incredible range of athletic dance steps. Lew would stun audiences with dramatic leaps, as Bill swirled around the stages, spinning feverish circles. Sandwiched between animal acts and headliners such as W. C. Fields, the Christensens learned the ropes of showmanship and entertainment, as well as developing a dominant athletic role for male dancers. That was not insignificant since early male ballet dancers had largely been used as balancing posts for prima ballerinas.

STEFANO MASCAGNO AND MICHEL FOKINE

To truly appreciate the genealogical lineage of the artistic philosophy that would later be embodied in Ballet West, good starting points focus on Stefano Mascagno and Michel Fokine, along with his family’s formative influences. In the late 19th century, Mascagno was schooled by his father, Ernesto Mascagno, Italy’s foremost ballet master and teacher. In 1895, then 17, Mascagno made his professional debut and in 1905, he came to the U.S. and settled with his American wife. He decided to establish the first dance school for any ballet instruction in the U.S. It set the platform for the Christensen brothers to learn directly from the young Italian master.

“It was all the time discipline. We would go into the studio, change clothes, fold our street clothes up, put them on the bench, put a pillow over them and we had to wear satin pants, stockings, a sash, and white, open shirt,” Mr. C told Verdoia in 1987. “Then we would go out into the hallway and wat ‘til he tapped his sticks, his baton, and the music started, and the girls would come out and they would go in and curtsy and we’d come in and bow. If we’d already been in and bowed to them, we’d go to the barre and stand waiting for his signal. It was a discipline that you couldn’t get by with today, but I’m grateful to have had.”

Mascagno’s instincts were impeccable, as Mr. C discovered. “When he set the stage first for us in the routines, he said, ‘Now here the girl have been back on pointe to touch their head,’ and we’d hold their hands over, and he said, ‘Now the applause here and you come out and you do this and they’ll applaud there.’ And I said, ‘How does he know they’ll applaud?’ But he always timed things, you know. You time things.”

Decades later, Mascagno’s deep intuition for timing and setting the energy for the climax became essential to the Ballet West formula. “Now I understand it very well, even when I hear a symphony concert, or watch a ballet, I know when there are points, but I didn’t know then,” Mr. C explained to Verdoia. As Verdoia succinctly summarized, Mr. C’s teaching style was the sum of every single experience in his life:the early music they learned from the grandparents and uncles, his family’s dance academy, Mascagno and Fokine (discussed below), the back breaking demands of vaudeville; his own choreography starting in Portland, continuing in San Francisco and culminating in Salt Lake City.

Mr. C studied with Fokine in New York City during the 1930s. According to Barbara Hamblin, a former Ballet West dance artist and ballet faculty member at The University of Utah who conducted an oral history (1994) with Mr. C when he was 92, “Fokine’s influence can be seen in Willam’s insistence upon beautiful and expressive port de bras … It has been well documented that Fokine was successful in eliminating tricks and acrobats from his choreography and changed, forever, the way we view ballet. Willam says he felt ‘freed’ as a dancer when he studied from Fokine.”

Fokine apparently was so pleased with Mr. C’s progress that he asked the young dancer to join his company. As Hamblin noted, Mr. C only danced with Fokine’s company for a short time because he wanted to return to Portland, where he was teaching and be with Mignon, his wife, and their son. Hamblin added that Willam was most impressed with Fokine “and was astounded by the abilities of Fokine in this area. He was capable of creating dramatic, mythic, romantic and abstract ballets; all expertly.”

TRANSITIONS WESTWARD

If one were to pinpoint when the first section of the direct path to the founding of Ballet West in 1963 was cleared and paved, it would be in 1932 when Mr. C went to Portland to set the stakes for a ballet company, while his brothers Harold and Lew stayed in New York City. Mr. C quickly stayed up with others who were blazing their own paths. For example, Lincoln Kerstein, who later became general director of the New York City Ballet, which started in 1934, brought George Balanchine and Russian masters to the U.S.

Ninety years later, the sustained fire of Mr. C’s vision at the time still seems extraordinary. In addition to a national landscape struggling under the enormous burdens of The Great Depression, he was always mindful of his wife’s condition with multiple sclerosis. Earlier, he married Mignon Lee, who was part of the quartet they founded in New York City, but then she had to give up performing because of illness. In 1938, when he was appointed ballet master at the San Francisco Opera, he commuted frequently between Portland and the Bay Area, while his wife stayed in Portland.

Then, in the midst of world war, five years later, he started the San Francisco Ballet, “the hard way,” as he recalled in a broadcast interview after he retired in the 1970s as Ballet West artistic director. “There were no grants, no help. So the dancers that performed in the opera, we had a manager and started booking, playing other cities.” They would tour the country but Mr. C said they always had financial problems. Opera was their mainstay but when the season was over he would book performances to keep the dancers busy. Thus, it made practical sense for him to choreograph the first American version of the complete Coppelia to the original music of Léo Delibes in the opera and then Swan Lake.

SAN FRANCISCO

In WWII, there were some sentiments that America should focus on modern dance rather than expend money and efforts to reconstruct classical ballet works, with others saying that perhaps the only place to really cultivate serious dance was in New York City. Some saw the idea of ballet in San Francisco as too great a financial risk that should be avoided.

Mr. C agreed, when Verdoia mentioned in the 1987 interview. In Portland, he experimented with Coppelia: “I didn’t know anything about the darn ballet, but I knew the music. But I had some white Russian friends, pre-revolutionary, which included Prince and Princess Vasilie [he was the nephew of Czar Nicholas]. So they wanted to do Swan Lake and I didn’t know Swan Lake, what they could remember as young officers in St. Petersburg. They had no money but they had nerve and enthusiasm.”

Mr. C went to Gaetano Merola, an Italian-born conductor and pianist who founded the San Francisco Opera Association in 1923. Mr. C had hoped that Merola would be open to his suggestions because the conductor had successfully organized local premieres of Tristan und Isolde and Turandot, and introduced the San Francisco audiences to Falstaff, La Fanciulla del West and Die Meistersinger. Merola told Mr. C that it would be nonsense to do Swan Lake before the opera season opens.

“For some unknown reason I had nerve plus some horse sense,” Mr. C said. “I went to the president of the opera, Robert Miller, who was a very wealthy man [president of Pacific Gas]… and I said, ‘Mr. Miller, my Russian friends [by the way he was friends with Prince and Princess Vasilie–everything had something to do with that), I said, ‘I’d like to do the Swan Lake two weeks before the opera opens, and I’ll take artistic responsibility, because it makes the company better, the better for the opera.’ He thought a while. I remember (he had silver dollars on his desk he’d raise after he’d drink) watching him think and he said, ‘Well go ahead, Christensen, and I’ll see. We’ll let you do that,’ because I was under the payroll of the opera, my salary, and we went ahead and did the ballet.”

Merola eventually gave into Christensen. Theodore Kosloff, a Russian-born ballet dancer and choreographer who was living in Los Angeles, heard the news and sent a telegram to his Russian colleagues. “He said, ‘It’s sacrilegious to do The Swan Lake, you know, with this American guy,’ and that didn’t make me feel happy,” Mr. C recalled, “but my Russian friends were patting me on the back, so we did it. The house was jammed.”

Mr. C was vindicated. Merola was happy. “I got a wire the next day from Theodore Kosloff, thanking me for doing it. I wouldn’t want to do it today because I had to learn everything I could about it. And I think it over, I can see some weak spots, but it was the first in America. So that’s the birth of The Swan Lake,” he told Verdoia, in 1987.

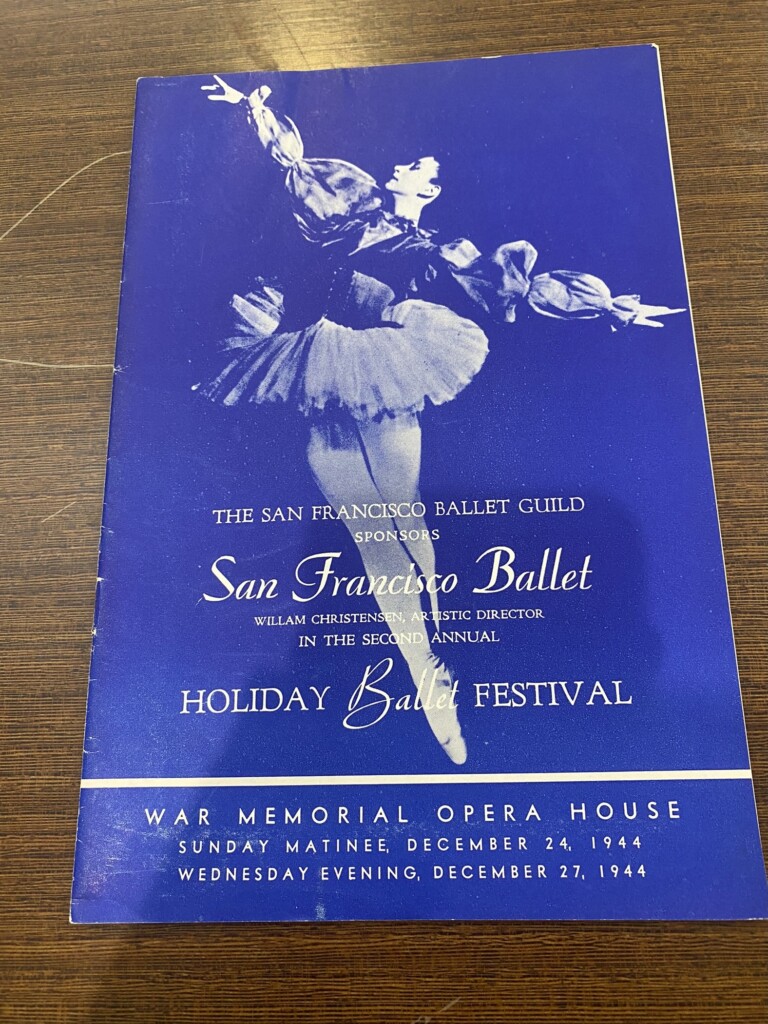

Photo: San Francisco Ballet.

THE NUTCRACKER

For many in Salt Lake City, the greatest source of pride has been Mr. C’s efforts to make the first American version of The Nutcracker, which he transported from its San Francisco premiere in 1944 to the University of Utah in the 1950s and eventually to its permanent spot in the Ballet West repertoire. After he retired, he was asked frequently in interviews about how he crafted his version of the holiday classic. He initially built the skeleton for it by cobbling details from recollections of dancers and choreographers as well as an edited version that was performed by the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. It was George Balanchine who told him about the Mother Buffoon number and the eight young dancers hidden under her skirt. Mr. C wanted a version closer musically to Tchaikovsky’s scoring:

So most of the steps are mine – my own creation. But musically, it’s absolutely right on the beam. As dancers become better, it gets better. And then, I change some, because I like to keep new vitality. The company is far better now than it used to be. So we can do much better.

He talked about walking in downtown San Francisco during the wartime years and hearing a recording of the Dance of the Mirlitons, which was being played in a store window display. He insisted on a strong visualization of Tchaikovsky’s familiar music: “And I thought, well, in the musical play, I used to say, if you could come out singing the tune, it’s a success.”

He talked to White Russians, including those who were pre-Bolshevik. Russell Hartley, who was then a 19-year-old dancer, created the costumes for the first production. Antonio Sotomayor, a South American artist, designed the backdrops which were covered with images of cupcakes, candy canes, ice cream cones and lollipops. The orchestral score had been obtained from the U.S. Library of Congress. The recording Mr. C was most familiar with came from Leopold Stokowski, the legendary conductor with the Philadelphia Orchestra.

The first Nutcracker was a huge success. A buoyant Mr. C wanted to stage Hansel and Gretel for the San Francisco Opera, as part of the general ballet repertoire. “And a stage hand said, “You’ll lose your shirt. ‘Cause they do it at the Met but out here it hasn’t succeeded.” Mr. C said the stage hand was right: “I personally lost $9,000. In 1944, that was quite a bit of money. And I went back to the Nutcracker and it’s never stopped.” In fact, it would be in 1949 when The Nutcracker came back to San Francisco and it has been presented annually ever since.

Perhaps the best explanation of how deeply The Nutcracker has been ingrained in Ballet West’s history from its earliest days came from Michael Onstad, who danced as the Snow Prince in the 1974 production. As a Salt Lake Tribune feature noted at the time, Onstad had danced as “a parent, a mouse, the host, a soloist in the Waltz of the Flowers and Dr. Drosselmeyer. This year [1974], he alternates as the aging doctor, Snow Prince, and in the Arabian and the Waltz of the Flowers segments.” Why did The Nutcracker matter every year, even if dancers knew the entirety of it by heart. “Nutcracker is like a report card,” Onstad explained. “It means I’ve grown a year… I’m excited to see what roles I’ll be doing… And I love magic. I read fantasy stories for pleasure… You can feel discouraged, annoyed, upset and you can hurt, physically from pain, but Nutcracker takes that all away.”

RETURN TO UTAH

With his success in San Francisco, Verdoia asked why Mr. C would return to Utah which had no ballet company at the time, no real dance theater and had a shaky commitment to the fine arts.

“Yeah I was daft,” Mr. C said. In 1947, the biggest company in the U.S. was in San Francisco but, as he noted, “ballet theater was a little offbeat and [there was] no support for touring.” Also, because of his wife’s illness with multiple sclerosis, he felt it was prudent to limit traveling which had taken up so much of his time.

Mr. C’s return to Utah in 1951 to start what would be the nation’s first university school in ballet at The University of Utah was not universally welcomed. The student newspaper picked up on comments that ballet was deemed as a commercial enterprise not worthy of university recognition and in an article, it was mentioned that Ray Olpin, the university president at the time, “had hired a toe dancer.” When Mr. C. came to the U., he left the San Francisco ballet in the hands of Lew and the company school to Harold.

Utah was not his only option at the time. Christensen’s success in San Francisco was widely noted, and he received offers from Stanford and the University of California to start a ballet school on their campuses. But, there was a huge sticking point: the offers specified that ballet would be housed in the school’s physical education department and Mr. C insisted that it should be part of the university’s fine arts programs. This would set a major precedent for dance education because even then modern dance was folded into physical education offerings. However, Ray Olpin, then president of the University of Utah, agreed with Mr. C. In fact, his blueprint for ballet education would eventually be replicated in other schools around the country, including Cincinnati and the University of Washington.

To ease into the new setting, Mr. C decided that instead of wowing newcomers with the tactics that kept him and his brothers from becoming targets of flying tomatoes in the vaudeville days, the first performance at the new school would not be a recital but instead a lecture demonstration:

I took dancers and showed them how they dress a stage, how movements fit with the music. From zero I make a sentence and a paragraph; so they can see how it grows, why there is a science to training. And this is not putting modern dance down, because the new modern dance is way ahead of what we see, there has to be a science first. You can’t be a writer without having a thorough knowledge of English and a knowledge of what has been written. You can’t be a great musician unless you learn to play some instrument. You can improvise on zero played by ear so long but it doesn’t go anywhere and the same with dance, so I had to explain that to these people.

THE FOUNDING OF UTAH CIVIC BALLET

But, Mr. C also thought about how to keep dance artists in Utah from going to New York City, San Francisco or elsewhere, because they were frustrated that there were practically no opportunities to get paid for performing in Salt Lake City. As he recalled:

I organized a ballet society here. And they decided to get together, this little group of dancers, and the University…well, they couldn’t because they aren’t a booking theatrical agency, they’re a teaching institution. But a very odd thing happened: I was watching television one night and saw Sol Hurok was … talking … about the Ford Foundation. And he was quite disturbed. He wanted more theaters, ‘cause he imports ballet companies and different artists, but the Ford would give a grant this time to ballet schools or people who could start companies. And I hadn’t heard anything about it.

In the early 1960s, he went to New York City in the hopes of pitching his idea for a grant but the Ford Foundation rejected it because it did not fit their preferred institutional criteria. Mr. C returned, this time explaining that the group he was forming in was nonprofit. The Ford Foundation became interested and offered a matching grant. Mr. C., who was then a full professor at The University of Utah, recruited Glenn Walker Wallace, the wife of John M. Wallace who was a banker and former mayor of Salt Lake City, to help found the organization. Foundation representatives visited Salt Lake City and sealed the deal, and the Utah Civic Ballet was born.

The five-year grant was $175,000. They had to raise $20,000 and annually they would receive $35,000 from the foundation. The timing was ideal, according to Mr. C. Ballet was coming of age at that point: “It was just getting its start. … There were grants for modern dance. But there was nothing for ballet in America. That was the first. The Ford Foundation gave a little stability.” By 1970, the Ford Foundation considered Ballet West in the Big Nine of the country’s ballet companies.

EARLY YEARS: UTAH CIVIC BALLET, NAME CHANGE TO BALLET WEST

In the earliest years of the Utah Civic Ballet, it was difficult to book performances in other cities. As Mr. C discovered, most cities would bring in ballet from New York City or San Francisco but it took a while for his newest company to take hold. “We weren’t very well known,” he told Ruth Draper, director of the Utah Arts Council, in his KBYU interview. “There was the Tabernacle Choir and the symphony making waves.”

But once the name change to Ballet West happened in 1968, it became an easier sell. “And that took down for a moment the barrier although now Salt Lake City is considered a cultural center. But that’s one of the processes that happened,” he said. “Because I remember when we took a company to Chicago for the first time, the critics said, ‘Where do these dancers come from? Did they feed them salt?’ And we played there three times and with good reviews every time.”

In a few short years, Ballet West consistently garnered excellent reviews outside of Salt Lake City. In 1967, Mr. C premiered his version of The Firebird, inspired by what he considered the most gorgeous music Stravinsky composed. After a Denver performance of Mr. C’s version of The Firebird, a Jan. 30, 1969 review in the Rocky Mountain News summarized it as “imaginatively stated, beautifully danced and exquisitely costumed, [and] it had all the color and drama many associate with an evening of dance. Janice James was an exquisite firebird who dominated the scene without once losing the fragile feel for the role. Rocky Spolestra was a dramatic Kostchie, a bit broad perhaps in his interpretation but effective. Dinne Cuatto made a lovely Tsarevna and Tomm Ruud was a capable Ivan.”

Later that same year, Saturday Review’s Walter Terry paid similar glowing attention to Ruud’s Mobile, set to Khatchaturian’s Gayne Ballet Suite. A trio for two men and a woman, the title was the acronym for Movements of Bodies In Linear Equipoise. “It is, of course, an abstract ballet, as fascinatingly non-literal as mobiles stirred by breezes or momentarily still,” Terry wrote. “The comprehension and exploitation of weights, pressures, leverages and balances are as absorbing as the designs themselves.”

Another Mr. C creation – Cinderella – brought a San Francisco Examiner critic to Salt Lake City when it premiered in April 1970. Alexander Fried called it “thoroughly enjoyable, alive and elaborate,” adding, “No big city in the East has ever originated a Cinderella choreography of its own, to follow the Russian and English versions of the 1940s. No other dance company in the West – and that includes San Francisco and Los Angeles – is at the moment capable of doing so.”

He sprinkled praise for Carolyn Anderson as Cinderella (“outstanding charm, warmed by pathos and sparked by spunkiness”) as well as for Ruud’s performance as the prince (“a very strong partner. His dance technique was out of the ordinary, in such trials as his long smooth series of bodily twirls and drops to the knees”). Of Mr. C., Fried concluded, “Always a fluid, secure choreographer, he now shows still further maturity and breadth on invention. One of his marked accomplishments has been to fit group and solo action unfailingly to the interplaying romance, sadness and comedy of Prokofiev’s brilliant music.”

The Denver Post’s Glenn Giffin followed suit in his April 14, 1970 review of a Ballet West performance, which included Irish Fantasy by Jacques d’Amboise, set to music by Saint Saens. Again, Ruud received praise, for showing “himself equal to d’Amboise’s demands, particularly with a series of batterie. And Janice James, his pretty partner, spurred him on with some bright dancing of her own.”

A side note is worth mentioning: resonant with Mr. C’s conscious efforts to embed a legacy into the idea of Ballet West as an artistic family, in later years, Ruud’s son, Christopher, would make his own imprint when he joined the company in 1998, after having spent the entire early years of his life at San Francisco Ballet. Today, the younger Ruud is now second company manager and rehearsal director at Kansas City Ballet.

THE 1970s

For Ballet West, the 1970s produced artistic triumphs, beginning with the tremendous response to the European tour in 1971 but the company also was fraught with many problems, especially when it was tied to finances and operating budgets. In the early 1970s, there were 38 full-time dancers, and they were paid 52 weeks a year with two weeks vacation. A top soloist was pulling $5,500 plus expenses.

EUROPEAN TOUR (1971)

In 1970, just seven years after its founding, Ballet West was already gaining national and international traction. The legendary choreographer Agnes DeMille spoke at the Governor’s Conference on the Arts, after a performance. She said, “Last night was a very replenishing night to me. … It’s a fine ballet. It is well-schooled, it is well founded, they are trained well,they are trained musically, they are decent, they are professional, they are hopeful, and I congratulate you.”

In the 1969-70 season, the company had taken to the stage more than 200 times. Ballet West’s schedule was so much in demand that Mr. C requested that organizers of the Athens Festival in Greece, who had invited the company to perform, could defer their invitation to the following year.

Mr. C said Athens was being pushed as a destination for the company, given the Utah Symphony had performed there with solid positive feedback. But, with his wife’s passing, Mr. C stayed behind and sent Lew in his place.

It turned out well, as the company’s tour of Europe in 1971 proved spectacular, as word of mouth spread about a ballet company from Utah which held its own on the continent. “The European tour put Ballet West on a different plane,” Mr. C said in an interview after he retired in 1978.

In Vichy, France, they performed in a theater built in 1864. The night before the performance, the company was invited to a performance by Marcel Marceau, the famous French mime artist and actor who heard many flattering comments about Ballet West’s European tour.

In Aix-les-Bains, well known as a resting stop for American forces during WWII, the company performed at the same theater where Tristan and Isolde received its French premiere. The town and its lake were the inspiration for the poem by Alphonse de L’Amartine that inspired the Swan Lake ballet.

The mayor presented Lew Christensen with a plaque while Tomm Ruud and Janice James brought the audience to a roaring ovation for their performance of Swan Lake. In Spain, in San Sebastian, the company performed at the Theatre Victoria Eugenia, and Ardean Watts conducted the chamber orchestra. In many performances, Jacques d’Amboise’s Irish Fantasy, a comic ballet parody, was rewarded with sustained applause.

The reviews were flattering everywhere. In Yugoslavia, a reviewer wrote, the company demonstrated “classical ballet with exemplary execution, extraordinary technique, excellent coordination and perfect discipline [that] belongs among the nine leading troupes in America. In Verona, New York Times correspondent Brendan Fitzgerald called the company “the cleanest, most precise corps de ballet that I have ever seen.”

In an Aug. 9, 1971 edition of Vjesnik, Croatia’s leading daily newspaper, the review carried the headline, Virtuosos on Tiptoe:

“Ballet West can boast of a superb corps, which dances with concentration, which attends to the music, and in which sixty hands move as one, and sixty legs as one, and which carries out every movement in perfect synchronization with the music, so that in some phases of the movement,it appears that one dancer has been multiplied 30 times.”

The Christensen family mark was prominent during the tour. Mr. C’s version of Coppelia was offered on several stops. Meanwhile, Con Amore, a work by Lew Christensen, a quasi-dance comedy in three acts which bordered on dramatic kitsch, according to one reviewer, confirmed Ballet West’s first-rate dancing ability.

An August 9, 1971 review in Slobodna Dalmacija, a Dalmatian newspaper, added about the Ballet West dancers, “There are no weak sisters.” An August 11, 1971 review in Večernji List, a Croatia newspaper, echoed other European critics about the corps de ballet and soloists being equal in excellence: “One is captivated by the versatile technique and refinement down to the last detail and the uniformity. Elan and the coordination of the ensemble are characteristics which adorn this ballet troupe. When in addition to all of these qualities, one finds such choreographers as Lew Christensen and, in particular, George Balanchine, then success cannot be denied.”

In a debriefing memorandum that came from the American embassy in Rome, the diplomatic observer called the August 13, 1971 performance of Coppelia in Verona extraordinary:

At the conclusion, they demanded curtain call after curtain call. Finally, they just rushed to the front of the Theater where they continued to cheer and applaud the dancers. The performers responded by trying to shake hands with as many of the spectators as they could reach. There was something almost electric about the whole episode. According to this observer’s Italian colleagues, such tributes to ballet performances are extremely rare.

A TENSE DECADE AT TIMES: THE 1970s

When KBYU’s Draper asked Mr. C about any regrets or mistakes he made during his tenure, he immediately mentioned “a revolution within the ranks” about being unionized. “And I would have, if they’d waited a little while, ‘cause I was watching the budget at the same time, and I had a series of general managers, who were novices too: let me put it that way.” As a comparison, Ballet West’s current annual budget of $18 million is two and a half times larger than it was in the 1976-77 season.

When Bruce Marks arrived in 1976 as co-artistic director and the company was in the middle of its summer residency in Aspen, Mr. C realized why he was not happy with the way things were going. “For a moment, I lost my way. And I’ve often thought of it; ‘cause I was having problems. I had half of a dozen dancers or a dozen dancers leave me all of a sudden. You know it was over… ‘I should be union’ or I didn’t pay “this one” enough and they went to the Labor Department and I had a whole stack of things,” he recalled. So I was [at] a very low ebb. But we pulled out of that and then began to get… right now, if I could get my hip well or something, I think I could…I would know what to do.”

Mr. C said there was a disconnect between the artistic and operational management at the time. There was talk about closing the company for three months to expand the margins in the budget. “And our general manager, not mentioning any names, went up to Minneapolis right while we were performing and discussed contracts and union with them [the dancers],” he recalled. “And we didn’t get a very good review, ‘cause the dancers were thinking of the contracts and the union, and arguing back and forth, rather than concentrating on the performance. That was a low ebb.”

For Mr. C, the biggest challenge in the 1970s was to ensure Ballet West’s longevity, which meant integrating a ballet school that would rise to the outstanding level to attract aspiring dance artists. With Marks’ arrival and his wife (Toni Lander) along with others, Mr. C saw teachers as godfathers and godmothers to ballet dancers and students.

In 1978, Mr. C reflected on why Ballet West had become essential in the community and why the constant drive for gathering support was good for the artistic direction of the company:

It is important: because if you have something unusual in your community, which makes the community richer to live in, you can brag a little bit about where you live in. It takes support. And although it takes a lot of teas and lot of gatherings, they’ve raised quite a lot of money; and they’re proud of it now and they stand behind it. In opera companies and ballet companies you need that support. The governors in the west knew that you must have certain cultural things: good education, orchestras, plays, ballets, operas because it makes the community richer. And then I like it too, because the guild people are in it, and they go elsewhere. And it’s good pressure against the directors. They have to be on their toes, they’ve got to understand what the audience likes, more or less you’ve got to lead the audience.

In 1981, the Christensen Academy celebrated its first anniversary. With management battles, tight budgets, the efforts to unionize dance artists and the constant pressures to raise funds and garner public support, Verdoia asked why Mr. C, who was in his mid-seventies at the time he stepped down, had waited so long to walk away from the top spot at the company.

Mr. C said that he didn’t know. He wanted to teach continuing education at the university and hoped to launch a scholarship program but university officials wanted students as teachers. Mr. C refused, believing that would take away vital time from developing artists to hone their techniques and skills. With that, he opened the Fortuna School in South Salt Lake.

Shortly after he retired in 1978, an interviewer asked him if his overriding goal was to educate or entertain. “Let’s say both,” Mr. C said.”If you only try to please an audience, I think it eventually degenerates.” When the followup question asked if his strategy was to pull out the warhorses, if he worried about whether or not the audience was satisfied. “So you’ve got to have war horses, and they’ve got to be better done each year, better than the year before,” he said. “But you must introduce new things. And that’s what takes judgment as a director. You can do certain things that have no chance at all of succeeding. So you have to have good taste, but if you don’t do new things, I think the art will … deteriorate.”

He mentioned the world premiere of Swan Lake in Russia was a failure but when it was revived it became part of the canon. He said something similar happened to The Nutcracker. “The audience in Russia said it was too symphonic,” he explained. “And we don’t think it was too symphonic.”

About modern pieces, he prefaced his comments by identifying himself as a theater man but then he quoted a conductor: “When you give a concert, you come in the house and there’s no curtain, there’s a podium, and the conductor comes in and they play. He says, ‘when you have a curtain it should become theater.’ And I think ballet and opera [are] theater.”

As for the theatrical strength of contemporary works and whether or not the meaning that an audience should take away is clearly expressed, he said contemporary choreographers should not blame the audience for failing to understand. “And frankly, the choreographer doesn’t understand,” Mr.C said. “Because when they do good work, that’s accepted. Carmina Burana: they like our version of John Butler. He’s a modern.” Ballet West premiered it for the company’s 10th anniversary season and it became an instant success.

STUDENTS

After Mr. C retired in 1978, many tributes included interviews with students and young dancers who came to Ballet West. One student said that he loves him like a father: “We really couldn’t get that close to him, but he was always concerned about the conditions we danced under and how we were doing and how we felt about our position in the company. So I mainly thought of him as a father who cared; not one I could get close to. But he cared more than I would think most artistic directors cared about your personality and how happy you were emotionally.”

In a similar tribute, Susan Sattler, who joined Ballet West in 1970 and later joined Brigham Young University as a ballet instructor, recalled when Mignon, Mr. C’s first wife, died just before the company embarked on its European tour in 1971 and her first year’s experience when the company was in summer residence in Aspen. She was not yet an official member and she remembered him introducing her to his wife, who had multiple sclerosis and was in a wheelchair. She talked about seeing how much Mr. C really loved her and cared for her.

And, she remembered how difficult it was at first to feel at home in the Ballet West studio: “He’ll show a combination, the steps that he wants us to do in class, and he’ll show it, and he’ll just talk through it really fast and you don’t know what he’s showing. And you’re scared stiff, ‘cause you don’t know what to do when the piano starts playing and everybody starts doing the step. So you just had to watch the older dancers that had been there and were used to his steps and his combinations. And then, after you were there awhile, you caught on to the steps that he wanted you to do. But at first, you just didn’t know what he was showing. But he gave me a lot of my dramatics. He brought my personality out on stage.”

She also talked about how upset he was whenever a dancer would make a mistake and swear. “And some of us used to laugh about that. ‘Cause he’d say a few words that he shouldn’t,” Sattler added.

Verdoia opened his 1987 program, which was recorded at Capitol Theatre in downtown Salt Lake City, with a student, who said, “He demands perfection. He’s also inspirational. He really knows his business. He knows how to build a dancer, not just give a class.” Mr. C honed his own response: “When you think you’ve reached perfection, decadence sets in. I don’t know any phrase better than that. You never reach perfection.”

Sattler’s earlier remarks were on point when one listens to what Mr. C recalled in his sit-down with Verdoia. “I’m a guy that loves life, drama; I like all the elements. If I teach a class, I don’t swear to be vulgar; I’ll say anything to get results. If somebody is taking a fifth position or a student’s in advance, I say, ‘That’s lousy.’ I don’t say, ‘Dear, sweet little girl, will you put your feet in fifth position?’ that’s housy, that’s stupid, you know. If somebody does something good, I’ll stop the class and say, ‘Hey, look, did you see that?’ because I know it’s a visual art. You can read about it until you’re crazy, but it’s what you see. It’s got to go through the eye to the brain, to the body.’”

Photo: Beau Pearson.

EDUCATION

By recognizing early on the importance of educating the audiences, something that also became a major driver for Utah contemporary dance institutional titans Repertory Dance Theatre and Ririe-Woodbury Dance Company, Mr. C would carry that forward to Ballet West. “We went to every school,” he recalled. “We went to a little spot called Manila [a tiny town of 324 population in the northern part of Daggett County near the border with Wyoming] and I couldn’t understand why people would come up there. And the Board of Education eventually helped us a little bit.”

Ballet West’s education and outreach started early in its history. In 1966, 30 dancers performed and demonstrated to 2,000 students in the Uintah Basin. By 1969, the program expanded to scores of performances in three states, reaching more than 90,000 students.

Today, education and outreach comprise one of Ballet West’s most prominent impacts. In his Dance Data Project interview, current artistic director Adam Sklute summarized the program, which reaches more than 100,000 students annually and is directed by Peter Christie, who danced with the company and trained with Jacques D’Amboise’s National Dance Institute. Noting that the goal is reach every elementary and middle school in Utah over a five-year period, Sklute added fhat the Our I CAN DO Program (acronym for Inspiring Children About Not Dropping Out) is dedicated to students in urban school districts, who are invited to create choreography in a collaborative setting. “One exciting offshoot of this program is that we are now beginning to see some of these kids coming up into our own Ballet Academy and one young man from the I CAN DO program is now in Ballet West II and represented Ballet West at the Prix de Lausanne,” Sklute said. “We also have programs like dance access for people with different physical challenges and abilities to learn to dance – a number of our company members and top-level students donate their time to this project. We also offer programs to teach ballet to the incarcerated.”

BRUCE MARKS

For any artistic director to step into Ballet West after Mr. C retired, the task would have been complicated in striking the ideal tone of leadership and artistic credibility, given the enormous stature of its founder. Bruce Marks, however, fit the bill when he was tapped to join as co-artistic director in 1976 a post he served for two years until Mr. C retired, who was confident with the progress of the transition.

Marks came from Denmark and was the first American to be a principal dancer with the Royal Danish Ballet. His wife, Toni Lander Marks, was born in Copenhagen and brought up with the Royal Danish Ballet. An expert teacher of the Bournonville technique, she became a principal academy teacher and would play a major role in facilitating the 20th century world premiere of Abdallah, a Bournonville ballet from the mid-19th century that had fallen into near-total obscurity. Among the works Marks set for Ballet West included Don Juan, Songs of the Valley, Don Quixote and Sanctus

When Marks succeeded Mr. C, if there were any concerns about the extent to which the founder’s shadow might have an impact on Ballet West’s continuous improvement in artistic development, those were addressed handily by works such as Sanctus, which Marks choreographed to a 1972 choral mass by David Fanshawe that was based on African folk music. When Ballet West performed it in New York City in 1980, a Saturday Review critic called it Marks’ “most important choreographic statement of his to be seen in New York.”

Marks constructed the work similar to the sections of a Catholic mass, which the Saturday Review noted that its intentions were to “look at and synthesize various faiths and expressions of faith. In the mix of religions, Marks attempts to convey our need–more apparent in ancient religions than in contemporary religions–’to dance out’ the magic of legend, the hope of myth, the passion of belief that characterize fervent religious expression.”

In a 1979 interview with The New York Times, Marks recalled when he told Mr. C about staging Sanctus. “Bill gulped. I knew that he thought it safest to stay clear of religious subjects. But he never tried to stop me,” he said. The biggest controversy was nicely summarized by The New York Times feature: “Then Marks got into trouble by informing the press that he considered Sanctus a balletic Jesus Christ Superstar, not realizing that rock musical was offensive to the Mormon community. Yet Sanctus was a success and some Mormon church officials made a point of assuring Marks that they did not find the ballet objectionable.”

Other Marks’ works won similar praise. Ballet News’ Clive Barnes wrote approvingly of Pipe Dreams, which Marks set to organ music by Louis Vierne, and Ballet West’s performance:

The choreography is brilliant–this is a company work where the ensemble is everything. And Marks demands blood. But the final effect is like bubbles on a summer day. The dance is guishing. You only have to see this to recognize that Marks has a real choreographic gift–how great rather than how real, time must tell. At present his people swim in a sea of dance–and that is wonderful and rare.

Marks continued to reinforce the Christensen sense of innovation and pioneer spirit. A June 1980 review titled, A New Kind of Western, in the Saturday Review could not have been more glowing: “Ballet West’s production of George Balanchine’s Pas de Dix has rarely been performed with such elan in recent years. Bournonville’s Flower Festival at the Genzano pas de deux, staged by Toni Lander, Marks’ wife and a great Danish ballerina, shamed almost every other American presentation of this Danish delight that I have seen.”

Some critics outside of Utah occasionally wondered if Ballet West would eventually become a “Balanchine satellite,” as The New York Times’ Anna Kisselgoff observed in 1980. But, such sentiments were dashed when the company offered three New York City premieres of works by Marks: Sanctus, Lark Ascending and Pipe Dreams.

Marks’ leadership and repertoire selections resonated with the meat of the point that Mr. C made in an interview after he retired. “A company should not have to apologize for being from Atlanta, or Houston, or Salt Lake City,” he said. “New York is overly sophisticated and chauvinistic. I’m not saying that audiences and critics should condone amateurish productions. They should strive for professional excellence and realize that it is possible to attain it outside of New York. That’s why I feel that what we are doing to Utah is important.”

When Marks was asked in a New York Times interview why he came to Ballet West, he said simply, “Bill [Mr. C] must be one of the best-liked people in the whole dance world.” In 1983, Ballet West scored another milestone, by becoming the first American company not from the East Coast to play the Kennedy Center Opera House.

ABDALLAH

One of the most historic moments in Ballet West’s artistry during the Marks years was the 20th century world premiere of Abdallah, a lost work of August Bournonville that the Royal Danish Ballet premiered in 1855. A fairy tale in the vein of Scheherazade, it became a project of love for Toni Lander, Marks’ wife who was an expert in the Bournonville technique. She and her husband had purchased the “lost” ballet, which included 16 pages written by Bournonville himself, for $150 at a Sotheby’s auction in 1971.

It had its contemporary premiere in February 1985 at the Capitol Theatre in Salt Lake City. “Abdallah emerged … as a triumph of loving scholarship and dedication to the highest standards of Bournonville style,” Lewis Segal at The Los Angeles Times wrote. “It is also, not incidentally, enormous fun as a dance entertainment: a love story replete with danger, comedy, magic, pageantry and enough ‘new’ Bournonville dances to reveal again the great Danish choreographer’s amazing range.”

When the ballet premiered in Copenhagen in 1855, Bournonville had just accepted a post in Vienna and had made notes from the score in hopes of restaging it in his new location. The story is straightforward: an Iraqi cobbler is in love and receives a magic candelabrum with five branches, but he is told that he can only light four of them to have his wishes granted. Of course, he cannot resist the temptation about what lies ahead if he lights the final branch.

Calling the production as filled with enormous taste and considerable splendor, Segal noted, “It would be extravagant to claim that Ballet West dances Abdallah with the peerless suavity and sparkle of the Royal Danish Ballet. However, this has always been one of the best regional companies in America and the dancers seem far more comfortable than other non-Danes with the special demands of Bournonville technique: the intricate legwork and nonstop fluidity of the combinations, the distinctive port de bras in jumps, the emphasis on mime. Best of all, they dance Bournonville like play rather than like some kind of test, and their enjoyment is contagious.”

There is a sad postscript to this, however. Three months after the premiere, Lander died at the age of 54. She had become ill just before the world premiere.

HELEN DOUGLAS

The 1980s produced significant first-rate additions to the Ballet West repertoire. Among them came from Helen Douglas, who later would choreograph work for ABT II, the Joffrey II Dancers and the Milwaukee Ballet. In an interview published after Douglas’ Mistress of Sorrows premiered, Marks explained the decision to appoint her as resident choreographer: “I told her we wanted to sign her to create three works over a three-year period. In astonishment, she asked why. I said, ‘we want you to do work you really want to do; if we made it a one-shot, you’d be worrying constantly about ‘success.’ The important thing to us is that you be true to yourself.’”

Douglas’ artistic excellence secured the Ballet West’s ongoing commitment to the preeminence of setting new works for the repertoire in-house. She created for Ballet West Esprit de Corps, set to music by Schubert while Mistress of Sorrows, was set to a Howard Hanson score and was a loosened interpretation of the Helen of Troy legend. She also set Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring.

Photo: Don Grayston, Salt Lake Tribune, courtesy of Ballet West.

OTHER ARTISTIC DIRECTORS AFTER MR. C

Four artistic directors have followed Ballet West after Mr. C retired in 1978. As detailed earlier, Bruce Marks came on board in 1976 as co-artistic director and the transition was completed after two years. John Hart, CBE, and Jonas Kåge followed. Adam Sklute, who danced with The Joffrey Ballet and was its associate artistic director, is in his 17th year as the artistic director at Ballet West.

Hart, who was born in Britain, took the reins in 1985 and, in an interview with The Deseret News in 1997, when he announced his retirement, he explained why he had never thought he would be willing to take the artistic helm at an American ballet company. “It wasn’t ever my intention to do so,” he recalled. “Partly because of the financial situations here in the United States, with the funding problems in the arts. I knew Bob Joffrey and Michael Smuin and watched what they had to do to keep their companies alive. In fact, if Mrs. Wallace (Glenn Walker Wallace, Ballet West’s co-founder) hadn’t have asked me to come to Salt Lake City, I don’t think I ever would have done it.”

Hart, who had been with The Royal Ballet, had come to Utah as guest artist to stage three ballets, when Marks left to join the Boston Ballet. It was Mrs. Wallace who convinced him to stay. In 1997, he told The Deseret News what he appreciated about the company: “The unique aspect of Ballet West is developing a catalog of works that suits the dancers as well as the audience here,” Hart said. “The company needed to take special heed to making sure the works were appropriate for the community. And the community here likes the 19th-century classics and immediate-past choreographers such as (George) Balanchine and (Frederick) Ashton.”

He added that it was important to emphasize the dancers as artists, not technicians. “I wanted to give the dancers roles for them to dance and play. I also wanted to spread the variety of works in the widest possible ways to bring the maximum [number] of people to see the performances. That’s why I encouraged three-ballet evening repertories.”

Following Hart, Jonas Kåge, former director of Sweden’s Malmo Opera Ballet, served as artistic director for nine years. During his tenure, Kåge introduced 32 new ballets, nine of them full-length productions, including his own stagings of Romeo and Juliet, Giselle, Swan Lake and Sleeping Beauty. In his staging of the Shakespearan classic, he used a live narrator before each act, to the scene by voicing the words from The Bard’s script. Kåge told The Deseret Morning News in a 2006 interview why he decided to pull up his stakes in Sweden and come to Utah: “I had only heard about Ballet West through its reputation at the time and knew there would be some adjustments on my part because I was in Sweden. And in Europe, the dance companies are state-run. In fact, the Malmo Opera Ballet housed the opera, the ballet and theater. It was a big elephant.”

Kåge’s tenure saw a slew of works that had never been performed in Utah prior to his arrival, including choreographers such as Hans van Manen, Glen Tetley, Amadeo Amodio, Richard Tanner, John Cranko and William Forsythe. Other major Utah premieres included Jerome Robbins’ Afternoon of a Faun, Balanchine’s Violin Concerto and Antony Tudor’s Echoing of Trumpets.

In fact, three other Tudor works also became part of the Ballet West repertoire: Leaves Are Fading, Offenbach in the Underworld and Lilac Garden — to the Ballet West repertoire. A company tour highlighted Tudor works when Ballet West performed at the Edinburgh Festival in Scotland in 2004.

BALLET WEST ON FILM AND SCREEN

Ballet West also found visibility on the Breaking Pointe reality series which aired for two seasons on The CW cable network. The series’ 15 episodes aired in 2012 and 2013 and drew a solid following. But, it also became a sharp reminder that ballet artists are more than just dancers.

A more compelling demonstration came in 2021, with the documentary series In The Balance: Ballet for a Lost Year, which was directed by Diana Whitten and Tyler Measom, well known filmmakers in the Utah community. The series dismantled several conventional myths about the ballet art form. In The Balance succeeded in making ballet less intimidating, humanizing both choreographers and ballet artists and revealing how the Ballet West community is striving sincerely to not just being socially relevant but also fulfilling meaningful goals of what inclusion, diversity, equity and accessibility truly mean in an art form that often is beset in its struggles to evolve and expand with a 21st century rhythm and meaningful context.

Indeed, the concerns about whether or not Ballet West would be able to proceed with its November 2020 performances, which included two world premieres, with audience capacity in the theater limited for social distancing purposes, anchored the intense emotional arcs of the documentary narrative. Sklute, Ballet West’s artistic director, worried that their efforts would be halted completely if Salt Lake County closed the Capitol Theatre with barely a day’s notice. In fact, after Ballet West had completed its run of the production featured in the series, the county did close the theater in response to the pandemic numbers.

The series also revolved around two choreographers who set he world premieres featured in the series: Jennifer Archibald, the founder and artistic director of Arch Dance Company and resident choreographer at the Cincinnati Ballet, and Nicolo Fonte, Ballet West’s resident choreographer. Episodes extended into other areas, which elicited some of the series’ most emotional epiphanies. The COVID-19 pandemic had accentuated the sense of vulnerability for artists. Indeed, the experience was difficult, especially for young artists or those in mid-career stages, trying to decide how to weather the storm. As the pandemic halted all live performances, some artists saw many months of work erased and now many realize that it might take two, three or even more years to rebuild the momentum they had achieved prior to the pandemic. And, artists were affected and shaped by other events outside of the studio: the largest wave of protests since the late 1960s in support of the Black Lives Matter movement and the tense anticipation of the 2020 presidential elections.

BALLET WEST AT 60

As Mr. C emphasized to never become complacent or stagnant but instead to find the ideal balance among the popular warhorses, the more historically significant and complex works and contemporary choreography, Sklute has carried the baton in the artistic relay with the same sentiments. “I’m always striving to create just the right ‘meal’ when planning a season: ‘comfort food’ like The Nutcracker and Swan Lake; fun meals like Dracula and the Family Series; and more complex historical works for the palate such as Les Noces or The Green Table; as well as yes, the Forsythe and Kylian masterpieces,” he explained in the Dance Data Project interview.

Likewise, Sklute, as with his predecessors going back to Mr. C reassured that Ballet West did not aspire to become a “Balanchine satellite.” He told Dance Data Project that “while we certainly do still present plenty of full-lengths and works by Balanchine, I have worked hard over the past 16 years to broaden that spectrum and give audiences exciting programming, both historic and new by a range of women choreographers and artists of color. It’s really about access and exposure for the audiences (and artists).”

At 60, Ballet West is as adventurous as during its formative years under Mr. C’s leadership. Last spring, the Ballet West production of Bronislava Nijinska’s Les Noces, a work which premiered 100 years ago in Paris, was a stunner for viewer and listener. It was a potent reminder that some of the greatest masterpieces created within the last century were set by women. Ballet West also took Les Noces to The Guggenheim Museum in New York City.

The 60th season resonates with Mr. C’s legacy. It opened with nearly 13,000 attendees during Ben Stevenson’s Dracula production run. The record-breaking sales represents a company high for performances other than The Nutcracker production. Ballet West has grown its subscriber base by 15% in the last year, contributing to three years in a row of subscriber-base growth by at least 10%.

For its forthcoming production which includes Mr. C’s version of The Firebird, there also will be a world premiere, Fever Dream by Joshua Whitehead, recently retired and long-term Ballet West artist. Whitehead also composed the music for the work, which originally was a workshop production for Ballet West Academy students. The company’s widely adored production of The Nutcracker will receive seven performances at Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. (Nov. 22-25), before returning to Utah for performances in Ogden and then in Salt Lake City (Dec. 8-27).

Next spring, the annual Choreographic Festival (June 5 – 8, 2024) will highlight Asian choreographers, artists, musicians, and companies. Among the slate works are a pair of commissioned world premieres, respectively, by Caili Quan and Zhongjing Fang. The Ballet West company also will take this program on tour at The Kennedy Center (June 18 – 22, 2024).

The 2024 portion of the season will open with a reprise of Swan Lake (Feb. 9-17), as conceived and produced by Adam Sklute, after original choreography by Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov, with additional choreography by Pamela Robinson-Harris, Ballet West principal rehearsal director, and the late Mark Goldweber

Spring will pop as a ballet blockbuster with Love and War (April 12-20, 2024), including a Utah premiere of Blake Works I, set by William Forsythe, among the world’s most foremost choreographers, as a work for the Paris Opera Ballet in 2016, with music taken from James Blake’s song catalog. The company also will reprise its production of Red Angels, choreographed by Ulysses Dove with music by Richard Einhorn. Four dancers and an electric violin, played by the original interpreter, Mary Rowell, one of only two people in the world to play this score, will perform. Rounding out the bill is Kurt Jooss’s 1932 work The Green Table, with a score for two pianos by Frederick Cohen.

The company’s Family Classics Series will return with Beauty and the Beast (March 29-30, 2024), conceived and produced by Sklute and choreographed by Robinson-Harris with Peggy Dolkas. Performed by Ballet West II and members of the Ballet West Academy, this production is designed for families and children looking for an introduction to ballet with a shortened run-time and narration. The run includes a Spanish-language narrated performance on March 30.

FROM BRIGHAM CITY TO INTERNATIONAL RECOGNITION

Mr. C recalled when Balanchine was in the Metropolitan, they had dedicated the season to presenting works by Stravinsky. Lew, his brother, was chosen to be the first Apollo for the American premeire

“When the concert was over — Stravinsky was conducting–he got up on stage and thanked Lew for being Apollo,” he recalled. “Lew was near tears: to go from Brigham City to being thanked by the great Stravinsky for doing Apollo in the Met during the big Stravinsky season. That’s a long ways, and I’ve often thought when I had San Francisco — when I was there, that was the second highest position to the Met in America, in fact, sometimes we’d top them. I thought, ‘I don’t know how I got from Brigham City to the San Francisco Opera with Larry Steinberg, Bruno Walter, and all the guys I was working with, I couldn’t understand it. I don’t yet.’” It is important to note that Mr. C was 85 at the time, when he recollected this to Verdoia in his 1987 interview.

In a feature published in the 1970s about Ballet West’s expanding international reach, the evidence was explained: “[Mr. C] can hardly step into another country without encountering an ex-pupil, as on his recent visit to The Royal Ballet School in London (where he met Valerie Valentine). Lew was creating a new full-length Cinderella and his version of Don Juan. The Christensens were acknowledged as leaders at the forefront of ballet in America.”

Mr. C died at the age of 99 in 2001 but his vision undeniably has been preserved and nurtured, as Ballet West looks to make permanent its phenomenal longevity in American ballet history.

This is a wonderfully written article. Transporting me back to my early dancing days with “Mr. C” I started out as a buffoon under the skirt with Rocky Spolestra (sp) as Mother Buffoon. Circa 1956. I grew into many other parts as the years went by. I loved Mr. C and still think fondly of my days and hours in class with him, from the time I was 10 years old to my college days at the University of Utah. His legacy is carried forward by so many of us teaching in our own schools. All because of the love of ballet he instilled in us. I’m in my 49th year of owning a school and still teaching.