EDITOR’S NOTE: Ririe-Woodbury Dance Company is celebrating its 60th anniversary during the 2023-24 season. This is a two-part feature, highlighting the legacy and impact of its two founders: Shirley Ririe and Joan Woodbury. For information about the opening Groundworks production and for a summary of the forthcoming anniversary season, click this link.

There are many access points to consider when chronicling the story of the Ririe-Woodbury Dance Company and its founders Shirley Ririe and Joan Woodbury, as this historic dance institution celebrates its 60th anniversary.

SLOVENIA, 1993

A very good example epitomizing what Ririe and Woodbury envisioned in making dance accessible to everyone is found in the 1993 tour to Slovenia, where the company gave four performances in locations including Ljubljana and Maribor. The Balkan Wars continued to rage in areas less than a two-hour drive from the republic. Some 70,000 Bosnian refugees were living in Slovenia at the time. The numbers included families who had no time to flee the war zone with their belongings, save for the clothes they were wearing at the time. Many children ended up being separated from their families while many adults had hoped they could be reunited with their children.

Olympic skier Andreja Leskovšek, a Slovenia native who was living in Salt Lake City at the time, admired the company’s work. She planted the seeds for the company to carry forward with the tour. The logistics were complicated, as the touring contingent would have to fly to Munich and then embark on a seven-hour drive to Ljubljana. As Woodbury described in her notes that later were published as a feature in a dance magazine, the clincher for proceeding with the tour was that the dancers would perform for more than 500 Bosnian children who were refugees that were housed in a collection center in Maribor. Another was a benefit concert to raise funds for refugee families.

Woodbury was rhapsodic about the first impressions during the drive to Slovenia — “the most gorgeous countryside, little houses tucked away in great green expanses of mountainous forestation. The further south we went, the more beautiful and quaint the country became. Beautiful tiled roofed stucco houses which felt that they had been designed for people with a zest for life. And not even the slightest indication that 100 miles south a vicious war was raging. A strange unreality settled over all of us.”

For the benefit concert in Celje, Ririe and Woodbury were taken in by the venue, which was more than 500 years old, “a little jewel box theater with a small but very deep stage.” It was not a theater that was particularly amenable for a company of contemporary dance. As Woodbury described, “The floor: there was no marley and the floor, made with 10’ wide pine planking, had in it the most gouges, holes, nails, cracks and staples that I have ever seen. The dancers looked at it in terror and awe. Great discussions were held about wearing Keds, with which we were prepared, but everyone felt the dances we had selected would look terrible in shoes.”

They looked closely at the floor, as Woodbury wrote, and decided to get a hammer and gaffer tape so they could prep it to dance on it in bare feet. She said, “It was a hoot.”

Leskovšek had joined the tour, serving as interpreter, and stood with Ririe and Woodbury in the wings, translating the words of the speakers on the stage, before the dancers performed. “The evening seemed to rush by … When the last dance was over the audience didn’t want to let us go,” Woodbury noted. “They clapped and clapped and clapped, not wanting the evening to end any more than when we did.”

The performance for the Bosnian children came the following morning, which would produce some of the most emotional moments for the dancers. The refugees were housed in old army barracks. It was early summer so by late morning, it was already hot. The dancers performed with their tennis shoes, as well as dark glasses to shield the sun’s glare. The stage was a large asphalt area which bordered some wooden benches and trees.

“We were immediately greeted by … lots of children, neatly and cleanly dressed, curious and seeming starved for affection and hope,” Woodbury detailed. “Women of all social strata, as evidenced by their clothes, were sweeping the asphalt sidewalks, others simply watched our progress through the grassy center of the complex.”

Leskovšek again was on site to translate. “From the onset it was a joy,” Woodbury recalled. ”We chose to perform dances which were funny, airy, special and athletic, showing a wide range of qualities.” Then the dancers interacted with the children who were being encouraged to improvise movement.

Leskovšek pointed to a small girl who had joined with the other children in the dance, while a woman nearby screamed for everyone to look at the girl. As Woodbury explained, Andreja [Leskovšek] learned that the child had been catatonic since she came to the refugee camp, and had not spoken to anyone or moved.

“People around her began to weep. We dancers know this can happen, we have seen things like this before, but here in the moment with our desire to give something of ourselves to these people who so needed the joy that the dance can bring, it was like a miracle,” Woodbury documented in her notes.

While the circumstances of the Slovenia tour were unique, the tour represented the performance model and educational formula that Ririe and Woodbury began establishing a decade before they founded the company in 1964 that bears their names. A critic in Slovenia described the experience: “They knew how to pour movement, voice and acting together into a noble comedy, worth the tradition of ‘commedie dell’arte’ and great clowns. The tercet of the two well-bred, etherical but in reality quite ordinary open-hearted ladies and a choleric malcontent is entertaining but not without irony and even a touch of bitterness.”

About the dancers, the Slovenian critic continued her praise with the dancers: “They are today a too-rare combination of professionals and enthusiasts in literal and the best meanings of the words. Their specific joint energy is perhaps nothing but genuine love for the dance that is fed with good relationships in a human and creative way and encouraging environment.”

‘A STORY OF TWO EXTRAORDINARY FRIENDS’

Similar words could be written today about the dancers, thirty years later. The point is this dynamic has always existed in the story of Ririe-Woodbury.

It is fitting that for the 60th anniversary, as part of its educational programs which have been as groundbreaking as the history embedded in its repertoire, the Ririe-Woodbury Dance Company has produced a delightful short-film — just shy of eight minutes — A Story of Two Extraordinary Friends, about the founders. The film targeting younger school audiences, which accompanies the company’s Dance Is for Everyone educational programs, was produced and directed by Sharah Yaddaw and Scott Hathaway of Wonderstone Films and written by Ai Fujii Nelson, Ririe-Woodbury’s education director. Adeena Lago, education assistant is working on a similar short film for upper school grades, which goes into more depth.

Nelson says that taking on the role as education director was a natural segue after having been a dancer with Ririe-Woodbury for eight years. “Half of the time spent in the company is dedicated to education,” she says. “I remember how invigorating the energy was when we performed for schools because it reminded me that we were doing the same thing that Joan [Woodbury] and Shirley [Ririe] meant when they developed the program around the idea that dance is for everybody.” It also became a wise way to educate and inspire future generations who would become patrons of the arts.

As with other outstanding independent arts institutions that have contributed to Utah’s impressive standing nationally and internationally, Ririe and Woodbury helped paved the creative highway and subsequently proved the enormous benefits of state funding for the arts; the value of the Salt Lake County Zoo, Arts and Parks (ZAP) Program and the unique strengths of the Professional Outreach Program in the Schools (POPS), which is managed by the Utah State Board of Education and sponsored by the Utah State Legislature. They set pedagogical standards not just in Utah but nationally and internationally as well.

Woodbury, who came from Cedar City, was the first person to receive a Fulbright fellowship in dance (1955-56), which made it possible to study in Germany with another contemporary dance pioneer, Mary Wigman. Ririe, who was born in Salt Lake City, also studied in Hong Kong and New Zealand on a Fulbright award. She studied with Elizabeth Hayes, who built the dance program at The University of Utah that ultimately has led to the golden age of dance in the state that continues to shine today. The legendary choreographers Alwin Nikolais and Murray Louis’ connections to Ririe-Woodbury started with Woodbury in 1956 at a workshop in Colorado. The three of them met for the first time and became lifelong friends.

As co-founders, Woodbury and Ririe complemented each other’s strengths that paid a wealthy sum, worthy of perpetuity. They pioneered dance education that encouraged improvisation and self-confidence in creative expression. Individually, they choreographed extensively, together producing more than 200 works for the company’s repertoire. They brought in the established leaders of contemporary dance while opening their doors to emerging artists whose works ultimately would find their way to stages nationally and internationally. From the instant the company was founded in 1964, both women ensured that the Ririe-Woodbury name eventually would be recognized, respected and emulated on every continent on the planet.

They also sharpened their skills for guaranteeing the durability of their artistic and educational visions. As correspondence and other materials from the company archives, which are housed in the Special Collections division at The University of Utah Marriott Library indicate, Ririe and Woodbury honed their acumen for effective persuasion, by making compelling appeals to raise funds for transcontinental tours, winning support for their trailblazing efforts in dance education and convincing legislators and governmental agencies to appropriate monies for arts programs. Many arts organizations leaders today would benefit tremendously by learning from their experiences because their vision was fully developed from the outset, which made articulating the persuasive message clear and to the point in its purpose.

The genesis for the company was set a little more than a decade before they founded the company. In the 1950s, Ririe and Woodbury shared a faculty position in The University of Utah’s modern dance program, an ideal arrangement given that both also were mothers of young children.

In a 2009 interview with Celia Baker for The Salt Lake Tribune, both women reflected on that time. “ It gave us double the energy in that job,” Ririe said. “We were both giving full time, but we were paid for half. We didn’t care about the pay, just what we could do, and it became very fruitful.”

“We’ve known each other and worked together longer than most marriages last,” Woodbury said. “We both believe the same things about dance. That’s what’s made it work.”

In 2003, for an interview with Jannas Zalesky, Ririe and Woodbury talked about how they made it work. They coordinated the births of their children in alternating years, to ensure that one of them would always be on hand to carry out the company’s creative and managerial responsibilities. They talked about their differences, as well. Ririe said, “I was born in Salt Lake City in 1929, the height of the Depression. My parents were both actors.” They had plans to move to New York City when their daughter was born but they revamped their plans. Her mother eventually became a business professor and author of seven textbooks. Ririe would tend to her younger siblings and in her free time would practice dance, which she had began taking lessons for when she was three.

Meanwhile, Woodbury, who was born in Cedar City in 1927, talked about the prominence of music in her family. Her mother was a pianist and church organist who played for practically every event in the community while her father raised cattle and sheep and ran his own business. “So from my parents I got both the aesthetic and the practical side of my nature,” she added. “I was a kid who loved to move. I played on the haystacks, ran through the fields, and climbed all of the trees. It was through movement that I understood life. Mom saw this in me and put me in a tap dance class at age 4.”

SYNCHRONIZED CAPABILITIES

Thus, it was easy to see how, as leaders, they synchronized their capabilities. Ririe and Woodbury also excelled at leveraging the company’s visibility for strategic public relations and the relentless need for fund-raising and sponsorships. The company’s international prestige became evident in its educational presence. For example, in 1974, Woodbury spent six weeks in Portugal, a trip that was funded by the Portuguese-American Cultural Committee, after being invited by the director of dance in Lisbon’s national conservatory of the arts.

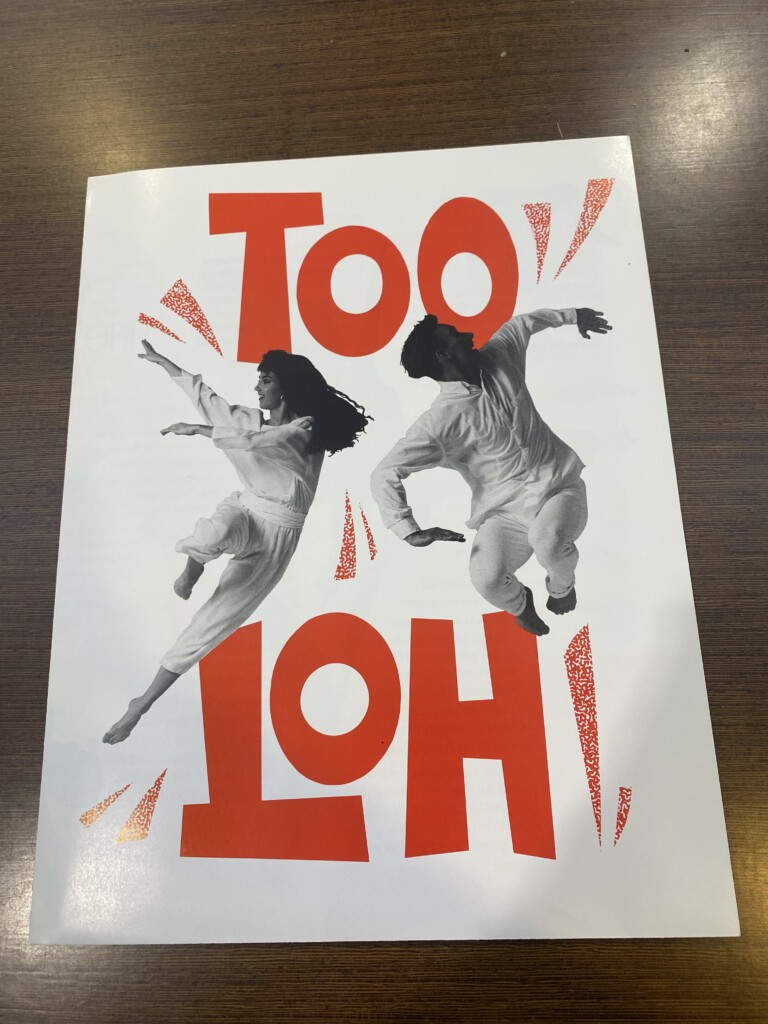

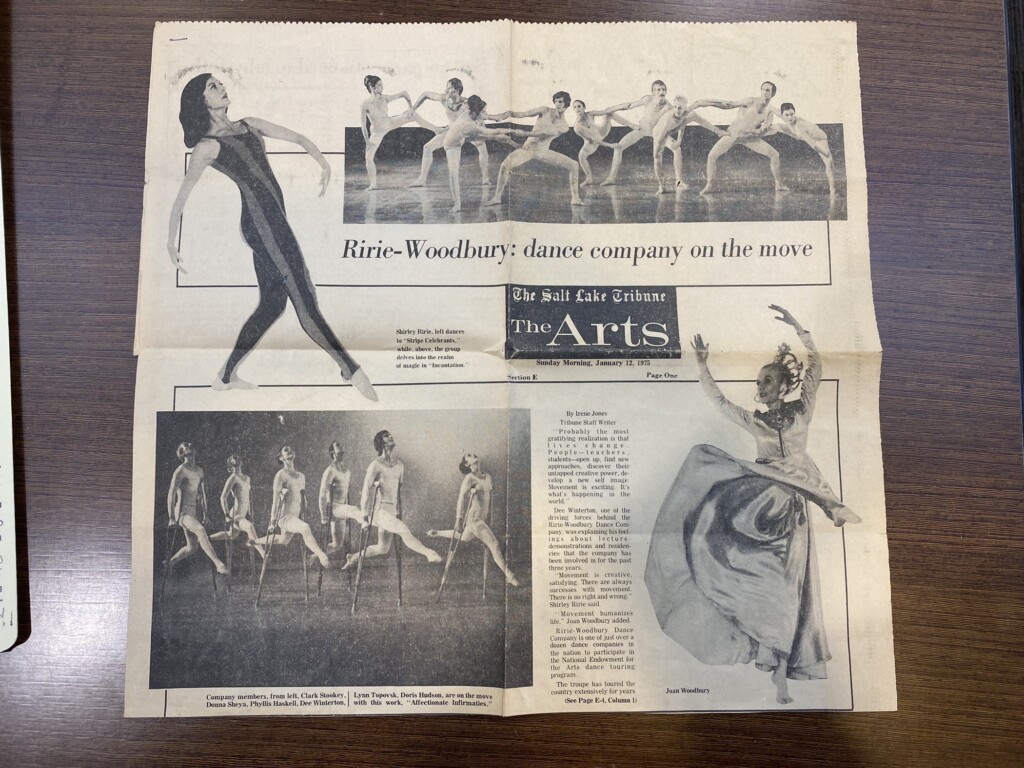

The company’s educational impact was featured in a January 12, 1975 article of The Salt Lake Tribune. “People who knew us are bringing us to their schools,” Ririe said. “The dance world’s small. It doesn’t take long for word to get around about who can give good lecture demonstrations and classes.” In 1974, the company had traveled to Minnesota, South Dakota, Missouri, California, Maine, Massachusetts and Hawaii. When the newspaper feature was published, Ririe-Woodbury Dance Company were set for a four-month tour and they were slated to return at the beginning of May in 1975. Why was the company in such high demand? The answer was easy: children and small stages scared many other dance companies, but not Ririe-Woodbury. “That’s where we have an advantage,” Ririe said. Utah has “lots of children.” Ririe was a mother of four and Woodbury was a mother of three, so it was obvious they never hesitated about performing before young audiences.

In the 1975-76 season, representing the NEA’s Artists-in-Education dance program, the company provided one-third of all the sponsored residences in the U.S., earning the title as the most traveled dance company in the country. Their South Africa success in 1977 led to an invitation for the 1978 Dance and the Child International Festival in Edmonton. Also, in 1978, the company went to what was then known as Yugoslavia, to participate in the 20th Jubilee Children’s Festival.

In a 1978 letter to U.S. Rep. K. Gunn McKay, who was then part of the Congressional delegation from Utah, Woodbury thanked him for supporting the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) and the Utah Arts Council. For the company, she wrote, “It has really tipped the balance on the scale and made it possible for us to become a company with a staff of 13 people involved within the arts in the state. We are able this year to reach the communities of Salt Lake City, Roy, Logan, Enterprise, Cedar City, St. George and Fillmore.”

Woodbury and Ririe were always sensitive to the fact that no programs were permanent guarantees, such as when talk emerged in 1978 that the NEA’s Artists-in-Schools program was in jeopardy of being weakened. In a letter to the NEA, Woodbury wrote, “I get very restless when I feel that the AIS program (which is very worthwhile, successful, and is making inroads) is being tossed around in the wake of changing times … and that for the sake of change the program may be displaced, or perhaps even worse, so watered down that those people who have helped it grow will lose their enthusiasm for it. Oh, not their enthusiasm for the artist’s role in the schools, but for a program which is no longer one of real quality. I hope this will not be allowed to happen.”

TIRELESS CREATIVE ENTREPRENEURS IN AND OUT OF THE STUDIO

Ririe and Woodbury treated their roles in the studio and in the business of sustaining the company with equal levels of dedication and sweat equity. In 1977, after KSL aired an editorial opposing federal funding for the arts, Woodbury was prompted to write a letter to L.H. Curtis, then president and general manager of KSL. She opened by explaining that when she was growing up in Cedar City, Utah, her father “opposed government interference in any affairs, stating that, as much as possible, things should be handled on a local level. So, my inclinations have, often unknowingly, been affected by his rugged individualism.”

She added, “How do we encourage these people, who are the seers of our time, to continue … to enrich our lives with music, literature, dance, painting, and drama … to stay deeply involved with their media without having to resort to other means of making a living and only being involved with the business of art in their ‘spare’ time?”

Woodbury then cited several examples of the public and private patronage of the arts from history. And, she noted how the national consciousness of the value of the arts to human existence has been happening in the U.S:

No artist wants to beg or be a freeloader, but he does want to work and there are periods in life when an artist must have support. It would be incredible if this support could come solely from the state and individual communities, but to this point it has not. There are many people in this particular community with great foresight concerning the arts (she named O.C. Tanner, John Gallivan, Dan Huntsman, Mrs. John M. Wallace, Wendell J. Ashton, Mr. and Mrs. Calvin Rampton, and even KSL’s L.H. Curtis) and their support has been meaningful. But as far as a total state consciousness, reflected in a tax base or in an individual level of giving, the need far exceeds the income.

This was the same year when the company had been invited as the sole representative from the U.S. to perform at the Eighth International Congress of Physical Education and Sports for Girls and Women in Capetown, South Africa. The company was struggling to fund the trip, a challenge that Woodbury admitted seemed virtually impossible to overcome, at the moment. “It seems incredible that, when such a singular honor has been bestowed upon a company, funds cannot be found to make the venture possible,” she emphasized in the letter to KSL.

Meanwhile, others were coming to Ririe-Woodbury’s aid in one form or another. For example, in an April 12, 1977 letter by then Utah Gov. Scott Matheson to the president of Pan American Airways, headquartered in New York City, he asked the airline to help defray the costs of transcontinental transportation to Capetown for the Ririe-Woodbury entourage.

THE VISION EXPANDS IN THE 1980s

In the 1980s, the company’s national and international presence continued expanding, in performing tours but also in developing educational resources for dance educators. They participated in the 1981 and 1985 editions of the Imagination Celebration at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. Their 1985 offering was The Electronic Dance Transformer, where the dancers emulated robots. One review likened the performance as bringing to the stage “pure television … a series of ten skits portraying people as computers. … The analogy is pursued relentlessly in a monologue clogged with rhyme and alliteration and delivered with school-marm cheer by a woman costumed in space opera fashion.”

Back home, innovative children’s programming flourished, when the company offered Shy Hag’s Magic Shadow Show as a Halloween tradition for several years, which was described as “modern dance’s answer to The Nutcracker.” The 1986 Video Visions production cleared a path for video’s role in modern dance performances, which has become common in the 21st century performance venue. The production featured live dance along with pre-taped dance sequences projected live on two large screens.

In a 1983 letter to a New Zealand dance program, Ririe outlined their development of a video and workbook outlining how improvisation in dance could be taught to junior high school students. “Modern dance teachers recognize the need for encouraging and nurturing creativity and the creative spirit, but some teachers, who have had no experience in teaching improvisation, lack confidence in their ability to stimulate creative growth in their students,” Ririe described in a research abstract. “They either feel that the task is too overwhelming, or that they do not have the necessary knowledge to design a course of study which will proceed logically toward an ultimate goal.” Ririe and Woodbury also went to New Zealand for the International Year of the Child Conference.

The film project was carried out under the aegis of the National Association for Instructional Television. Dennis Wright, a former company dancer, was tapped as the teacher. To summarize the case in 1983, the point was clear: “Dance in Utah is incredible, particularly on the level with three full-time touring companies, the Children’s Dance Theatre (under Mary Ann Lee) and additional touring companies in the University in both ballet and modern dance. … With Virginia Tanner’s work and the heavy involvement of many of us here in Artists-in-Schools, Utah is a real center for that program as well and perhaps THE center for quality children’s work in the nation.”

In 1991, after a tour in American Samoa on its largest and most populous island of Tutuila, Ririe wrote about the company’s experiences for Tradewinds, a publication of the Consortium for Pacific Arts and Cultures, which included what she thought were the most satisfying performances during their time there, in the remote villages of Vatia and Afono. About teaching the workshops, Ririe wrote, “I decided that much of what I was dealing with was the Samoan culture and the way these teachers interacted with one another in their villages and schools. This was something I began to understand more and more as each day passed.”

She recalled one teacher, a male who appeared to be in his late forties who had attended all three workshops one day. He even volunteered to move furniture before and after each session. “He was absolutely wonderful in the workshops, he was athletic, imaginative, fun loving,” she explained. “He did some very clever comedic actions when it was appropriate and ‘brought down the house’ performing for his fellow teachers. He was sometimes shy, but always watching and absorbed.”

Ririe noticed that he had set up a video camera to record the show. “And, something I really loved,” she added. “He brought his whole class of first graders to this performance, in the back of his truck. This story is worth the whole residency to me.”

The company also went to Hawai’i, a state where they already had performed in the 1970s and 1980s, at the same time when they visited American Samoa. Ririe summarized the experience of the company’s visit to the Nimitz Elementary School in Hawaii, which included a performance for an audience of 700. She wrote, “One child from my first grade class came up to hug me with her body shaking from crying. That contact put a flood of tears out of my eyes as well. How close bonds can come in just a few hours.”

There was no area of the world that Ririe and Woodbury overlooked for organizing tours for performances and educational outreach. Perseverance was ubiquitous. In Asia, the company performed in Singapore and became the first American modern dance company to perform on mainland China.

Even in 1980, when South Korea was under martial law, with widespread riots ongoing in the cities and many of the nation’s colleges and universities closed, the company had corresponded with Wansoon Yook, who headed up the department of dance at Ewha Women’s University in Seoul, about a possible residency. When the company was preparing for a tour in early 1987 that would take them to American Samoa, Guam and Saipan, Woodbury once again reached out to Yook but logistics and funding were too complicated to arrange in time.

The company went to Korea and Mongolia in 2018. Prior to the opening of its 55th season, the company traveled abroad as cultural ambassadors, part of DanceMotion USA℠’s cultural diplomacy program, which was coordinated with the U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs and administered by The Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM). Ririe-Woodbury was one of three American dance companies selected for the program.

The experience reaffirmed the central significance of the legacy Ririe and Woodbury had nourished since the beginning. In a 2018 interview with The Utah Review, Daniel Charon, current artistic director, said, of the impact of the trip, that the cultural mission in Asia confirmed that “we really don’t need to change the wheel.” But, he added that it also enlivened and strengthened everyone’s sensibilities and sensitivities about making the connection to different audiences and demonstrating how dance for everyone can be anything and everything instead of being intimidating and discriminating (when based on ability and experience). This became the seed for the company’s Moving Parts Family and Sensory Friendly matinee series, which continues to this day.

Unfortunately, some modern dance purists could not abide the innovative artistic directions that Ririe and Woodbury took for the company. For example, the April 1990 of Pizazz and Percussion turned out to be a scintillating experience of dance theater and lvie music, featuring The Saliva Sisters, The University of Utah Percussion Ensemble, The Lymph Notes, guitarist Todd Woodbury and actor Lynne Van Dam. Among the works were Ririe’s Madame X, based on a painting of the same title by John Singer Sargent and Woodbury’s Refusal to Dance, which featured poetry by Gayle Sternefeld, featuring actor Van Dam and guitarist Woodbury. Also, there was Woodbury’s Ladies, Ladies, Ladies, which featured The Saliva Sisters, The Lymph Notes and a faculty quintet from Westminster University.

Finally, there was Ririe’s Banners of Freedom, a work which the company will perform in the Groundworks production that will open the 60th anniversary season. Premiering just months after the Berlin Wall came tumbling down, it was an artistic tribute to those who were part of history unfolding on live international television. Described by one critic [Horizon’s Jerry Wroble] as “the purist’s dance of the evening,” it was “enhanced by beautiful banners streaking across the stage.”

Meanwhile, a review by Salt Lake Tribune critic Scott Rivers was so negative that veteran dancer and choreographer Robert Blake, who was splitting his time between Salt Lake City and San Francisco, wrote a letter, calling out Rivers for his inept unwillingness and inability (Blake’s words) to comprehend the production. “Obviously a reviewer may have a different opinion from that of other observers on some aspects of a performance. However, the consistent way (except for a short ending paragraph) in which Mr. Rivers down-rated this program was appalling,” Blake wrote. “When I read his review, my immediate reaction was that he either did not have a real understanding of theater dance, or that he had a grudge against Ririe-Woodbury and was using the influence of his article to disparage them.”

Meanwhile, for the same concert, Wroble wrote in Horizon that some modern dance purists might have found it disappointing “but for those wishing to be entertained and not too particular about the way in which they are entertained, the evening was a success, much the way a good Margarita is a success.”

THE ALWIN NIKOLAIS COLLABORATION

The 1980s also became a thrilling decade for exploring dance theater and multimedia performances. At the time, Ririe-Woodbury’s residency was in the Capitol Theatre in downtown Salt Lake City. Each year, they toured between 21 weeks and as much as 40 weeks in some years. The company also conducted an annual dance summer workshop at Snowbird.

Most notably, Ririe and Woodbury institutionalized the legacy of Alwin Nikolais into the heart and soul of their company’s repertoire. Ririe-Woodbury took a unique role in preserving Nikolais’ work. After Nikolais’ death in 1993, the Nikolais/Louis Foundation split into two entities but it has remained that Ririe-Woodbury is the only American dance company to absorb the works into its permanent repertoire. The decision was made by Murray Louis, who was Nikolais’ creative and life partner for many years, and Alberto del Saz, a former Nikolais company dancer who has ensured that his mentor’s artistic legacy is sustained.

Nikolais already had a long association with dance in Utah and had known about the foundations being set by the two choreographers. He taught summer courses between 1961-63 and 1965-67 at The University of Utah. He received a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation in 1962 to mount Totem for university dance majors. When the company was formed, Nikolais gave them Striped Celebrants from Totem and Louis gave Ririe and Woodbury Suite de Danse and Landscapes. Later, parts of Liturgies (one of Nikolais’ most celebrated works which also will be featured on the forthcoming Groundworks production) were taken from Totem. Nikolais also was an advisor for the Rockefeller Foundation funding that led to establishing Repertory Dance Theatre in 1966, the first sustainable company of its kind outside of New York City. Linda C. Smith, one of the founders who continues to lead RDT to this day, also had studied with Ririe and Woodbury.

Louis wrote in 2003 about how Nikolais (‘Nik’) cemented the ties to Ririe and Woodbury. “Nik had gone to Salt Lake City for six summers during the 1960s, and have evolved much of the basis for his aesthetics and vocabulary on Joan and Shirley and their workshops.” He continued, “There he defined a vocabulary that would take dance a step away from the vague, often careless and indulgent, limitations the ego presented and instead relate it to the elements of space, shape, time and motion. He distinguished dance from general movement by identifying the nature of its interior motion.”

The Nikolais relationship has flourished through every decade. The company premiered two works by Louis in 1981, gave the Utah premiere of Physalia, and The Alwin Nikolais Dance Theater performed with Ririe-Woodbury dancers in 1984, then the first collaborative performance for the Nikolais company. It was Nikolais’ first appearance in Salt Lake City since 1969. The event would be repeated three years later: Together Again, along with guest artists Danial Shapiro and Joanie Smith who were former soloists with the Murray Louis Dance Company.

Years later, the case example of a Nikolais/Louis Legacy Workshop illustrated the unique bond that was established, an effort that everyone in the company was wholly invested in making it a reality. Ririe, who also had a lifelong affinity for the aesthetics and pedagogy of these two mentors, cited her colleague’s efforts in organizing the workshop. “Joan has a fierce dedication to the work of Alwin Nikolais. It was largely Joan’s energy that brought the Nikolais Festival into being,” Ririe explained. “True, it was because of Murray Louis that our company was chosen to mount an evening of Nikolais choreography and it was because of Murray’s generosity that it was even possible. But without Joan’s persistence in writing and obtaining grants and her skill at organization it never would have happened.”

Daniel Charon, the company’s current artistic director, says Nikolais’ works continue to demonstrate the famed choreographer’s prescient vision that inspired a broad movement of multimedia dance compositions performed by the Blue Man Group, Cirque du Soleil, Pilobolus and Momix. “The roots of his work have so many influences today,” he explained in an earlier interview with The Utah Review. “He directed and conceived every element including multimedia, costumes, music and lighting techniques in his work, in addition to the choreography.”

Nikolais was the dance world’s counterpart to Richard Wagner, the German composer of opera in the 19th century who conceived his work as Gesamtkunstwerk (translated as, total work of art).

“Like a Steve Jobs of the theater, Nikolais was a master mind,” Rachel Straus described him in a Musical America website post. “Indeed, before the invention of laser beams, light shows and computer-generated images, Nikolais figured out how to rig a lighting plot and employ unconventional material to generate that which hadn’t yet been discovered by engineers. Instead of clicking and coding, his dancers designed the space with their bodies, and props, to produce a vortex of intersecting lines. Nikolais’ futuristic artwork is at its most dazzling when the dancers frame themselves inside their own sets designs (or interfaces).”

In many ways, Nikolais expressed the gist of the meaning in Marshall McLuhan’s famous phrase, “the medium is the message.” Charon noted that Nikolais would incorporate the old film strip projectors that used to be the essential equipment in every classroom. For the company to return to a fresh performance of Nikolais’ work is not that much different from the nostalgic affection many enjoy in rediscovering vinyl records or the art of writing a letter by hand or the resurgent interests in calligraphy.

Among the Nikolais works in the Ririe-Woodbury repertoire, which span a 30-year creative period, include Tensile Involvement (1955), Gallery (1978), Mechanical Organ III (1983) and Crucible (1985). As with its opening Groundworks production for the 60th anniversary, the company has periodically presented Nikolais’ choreography locally, nationally and internationally. Regarding a 2016 performance in New York City, a review in The New York Times noted that, “the performers, generous and game, bring the dances into the present. They also work as a group, and this all-for-one mentality seems crucial: Nikolais, who revered abstraction, stood for motion over emotion.”

In Tensile Involvement, for example, the dancers are attached to elastic strings on their hands and feet so the movements create the impression of watching the performers move in planes of infinite space. Lighting takes on an even more prominent role than usual in staging, as in Gallery, for example, where the effects generate a host of presumed apparitions of floating heads, sometimes resembling an arcade shooting gallery at a fair or amusement park. In Crucible, a mirror emphasizes disembodied effects as the dancers spiral and fold themselves continuously. Mechanical Organ is like a mischievous exercise of dance play, rendered in several sections, as dancers form the shapes as they link to each other that almost seems to recreate the movement of a calliope being played.

Physalia is a 1977 work originally choreographed by Moses Pendleton and Alison Chase, co-founders of Pilobolus. Physalia incorporates extensive acrobatic choreography to suggest the imagery of the work’s title, which refers to a Portuguese man-of-war. It’s often mistaken as a jellyfish but, in fact, it is what marine biologists refer to as a siphonophore, an animal made up of a colony of organisms working together – an apt description of the creative intent behind Physalia.

The artistic bond between Nikolais and Ririe-Woodbury is unquestionably embedded within the instinctive DNA, a trait that has been carried through every generation of dancers who have performed with the company, up to and including the core of six artists who are performing during the 60th anniversary season.

In a 2004 review for The Dance Insider, Paul Ben-Itzak prefaced his assessment with the assumption that there should be a “difference between the work of a master choreographer who has a technique when performed by dancers who have trained for years in that technique and dancers who simply learn the choreography for given dances.”

Calling the Ririe-Woodbury company’s performance of Nikolais’ works in Paris stellar, Ben-Itzak explained that the experience validated his assumption and the fact that the dancers matter in the results. “Before I’d seen this company in the work, I’d pressed that point because, frankly, suggesting that this was the Alwin Nikolais Company – as the Joyce Theater did for last fall’s New York performances – seemed to promise something that the actual company performing the work couldn’t necessarily deliver. Now that I’ve seen these dancers in the work, if anything I think this company should be wearing its own name with pride. … [The] R-W dancers definitely gave this work as it absolutely needs to be given.”

To wit: Ririe’s recollections about the Paris performances capture this point. “Many knowledgeable people spoke to us about our show,” she wrote. “Because they know Nikolais so well, their praises were much appreciated. They felt we performed the work beautifully, they felt the company was fresh and the dances looked very contemporary. The reception kept building and our last show in Paris garnered 28 bows.”

Rave views of Ririe-Woodbury’s performances of Nikolais’ works followed later that year at the prestigious Edinburgh International Festival, where members of the Ballet West appeared separately in offering a retrospective of choreography by Anthony Tudor. Depending upon the Scottish press publication, Ririe-Woodbury earned the highest possible ratings, of four or five stars, in every review.

SUSTAINING THE ARTISTIC VISION

Looking to the future, Ririe and Woodbury, in the late 1990s, set the stage for passing the artistic baton. There have been three artistic directors since the turn of the millennium. From 1999-2001, former company dancer Emmy Thomson, who currently is at The Waterford School, was associate artistic director. During her tenure, The Salt Lake Tribune nominated her as ‘Best addition to the Salt Lake City dance scene’ in 2001 and cited her choreography for Invocation as ‘best of the year.’

In 2002, Danish choreographer Charlotte Boye-Christensen was appointed artistic director and served for 11 years. During her tenure she commissioned the work of internationally renowned choreographers: Wayne McGregor, John Jasperse, Alicia Sanchez, Bill T. Jones, Susan Marshall, Karole Armitage and more. She also created 22 works on the company, co-developed a new educational program titled “The Place” project and toured with the company to 33 cities across the U.S. She is currently head of the dance department at Cornish College of the Arts in Seattle. Boye-Christensen will set a new work on the company’s current dancers, which will receive its premiere in the season closer next April.

During Thomson’s tenure, the company moved its residency from the Capitol Theatre to its current location at the Rose Wagner Center for Performing Arts. In 2001, the company gave its first performance in the Jeanné Wagner Theatre, which included performances of Shapiro and Smith’s To Have and To Hold, along with a world premiere of Sean Currin’s Metal Garden and works by Pascal Rioult and Della Davidson.

When Daniel Charon arrived in Salt Lake City as Ririe-Woodbury Dance Company’s artistic director, the internationally known dance institution was marking its golden anniversary. The past decade has certainly magnified Ririe-Woodbury’s distinguished reputation. During Charon’s tenure to date, the company has presented 20 original dance works by him, as well as pieces from nearly 50 guest artists.

It has been as exciting a decade under Charon’s artistic leadership as the first 50 years had been. Visiting choreographers have included some of dance’s most widely known rising stars: Netta Yerushalmy, Joanna Kotze, Raja Feather Kelly, Keerati Jinakunwiphat, Culture Mill (Clint Lutes, Murielle Elizéon and Tommy Noonani) and Yin Yue. Ririe-Woodbury also has generously opened its creative spaces to local artists, including LajaMartin, Ann Carlson, Molly Heller, Stephen Koester and Michael Wall, among others. Dancers from area universities including Utah Valley University and The University of Utah have joined the company’s dance artists in concerts. Groundworks will feature guest dancers from Brigham Young University. Charon collaborated with the Sale Lake Electric Ensemble to create two evening-length works, which included both live performances, recorded original music and the ensemble’s internationally acclaimed interpretation of Terry Riley’s minimalist masterpiece In C. A third collaboration with the ensemble is set for April 2024. One work, created for family audiences, brought in Dallas Graham of the Red Fred Project and the Flying Bobcat Theatrical Laboratory. This past spring, the company premiered an evening length work of dance theater about saving the Great Salt Lake (To See Beyond Our Time), in collaboration with Charon and stage director Alexandra Harbold. During the pandemic, with live performances grounded for many months, the company produced filmed concerts, including one with Repertory Dance Theatre.

Charon is astute and unfailingly sensitive to the unique character of the Ririe-Woodbury soul that its founders nurtured and took meticulous care of during their long tenure. “It has been a satisfying joy to generate so much work during the last nine to ten years, especially with dancers who support each other, have exceptional character and work ethic,” Charon said last year in an interview. In the years surrounding the pandemic, the experiences of coping – which have included auditions via Zoom and filmed concerts streamed on demand – actually strengthened the company’s resilience and ensemble chemistry. Charon added that among the most significant takeaways as he completed his first decade with Ririe-Woodbury is how he has inculcated the values of spontaneity and trust in his instincts as a choreographer — a familiar trope that signifies the legacy of its two founders. Certainly, Charon consistently has acknowledged how much the creative process for setting a new piece involves genuine collaboration with the company’s dance artists.